The Stress-Test Rate Increases to 5.25% on June 1

May 25, 2021The US and Canadian Employment Data Disappoint (Again)

June 7, 2021 The mainstream market consensus believes that higher-than-expected inflation will force central banks to hike their policy rates more quickly than they are forecasting.

The mainstream market consensus believes that higher-than-expected inflation will force central banks to hike their policy rates more quickly than they are forecasting.

If that happens, our mortgage rates will rise above today’s levels, and anyone who locks in a fixed-rate term now will likely come out ahead.

That said, a (growing) minority of market participants, which includes our central banks, continues to argue that our current inflation run-up will prove transitory, and that fears about sustainably higher inflation are overblown.

If they are proven right, today’s variable rates will likely end up being cheaper than their fixed-rate alternatives.

In today’s post, I am going to lean on two excellent John Mauldin newsletters to summarize both sides of the inflation argument. Mauldin just held his annual investment conference, which attracts first-rate experts across the economics/investment spectrum, and future inflation was a hot topic this year.

Let’s start with a summary of the key points that were made in favour of higher inflation:

Deglobalization – Globalization has steadily reduced the price of goods for about 20 years, but we are now experiencing deglobalization. Trade wars started this trend, but the pandemic has accelerated it by exposing “how vulnerable … ocean-spanning supply chains can be to events on the other side”. When companies in countries like the US and Canada bring production back home, their costs will rise.

Higher Shipping Costs – Shipping costs are higher because “many transportation companies went bankrupt over the past few years” and that left fewer survivors to service today’s surging demand for goods. In addition to that, the global economy is not yet optimized to accommodate “new consumer preferences”.

Higher Labour Costs – The pandemic decimated many service-sector jobs and those that remained were less appealing to workers because of “new hazards and hassles of in-person work during a pandemic”. At the same time, the emergency government support that is being paid to the unemployed is generous. Those combined factors have forced companies to raise wages to entice workers back, and because “wages are sticky”, those pay increases will be tough to pare back in future.

Pent-up Savings – Generous government transfer payments have led to a spike in personal savings rates, and as economies re-open, the release of those savings will cause a surge in demand that will outstrip supply and push prices higher.

Rising Raw Material Costs – The price of raw materials has spiked, in some cases back to percentage increases not seen since 1980 when inflation was 13.9%. Higher raw-material costs will put upward pressure on the price of finished goods.

Inflation Expectations Will Become “Unanchored” – As cost pressures build, businesses “are going to become comfortable raising prices” and at that point, inflation expectations will become “unanchored”. This is seen as the point when inflation could really take off.

Central Bank Guidance – The US Federal Reserve remains adamant that it will hold its policy rate steady until 2024, and that promise is fueling speculative behaviour that is also pushing up prices.

Now let’s look at the points made in favour of the view that the current inflation run-up will prove temporary:

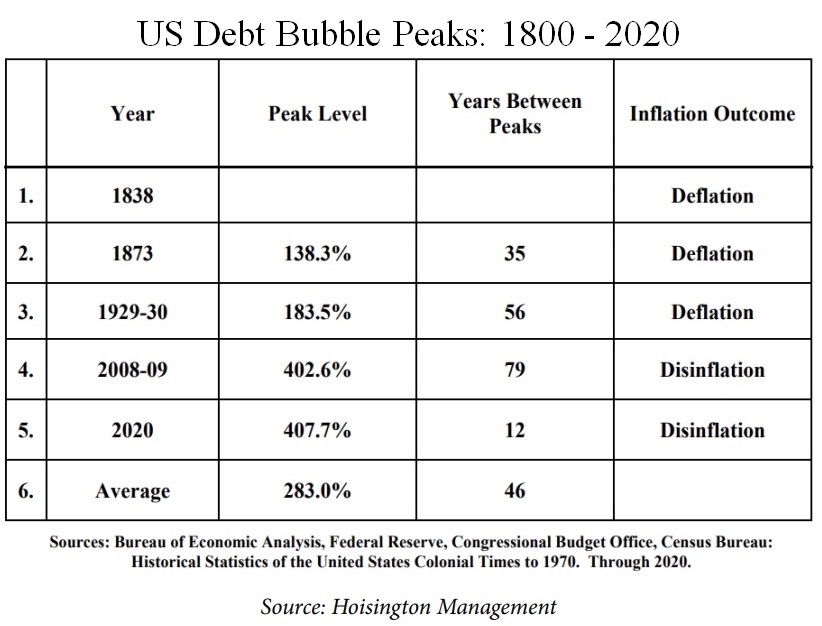

High Debt Levels – Economist Dr. Lacy Hunt explains that “excess debt suppresses economic growth, without which demand can’t rise enough to generate inflation or push up interest rates over the medium term. This is a structural problem, which at this point we really can’t fix.”

His chart below summarizes what happened with US inflation during the five major US debt bubbles that have occurred over the past two hundred years. (The US and Canadian debt-to-GDP ratios are now at record highs, which makes our current debt bubble and its deflationary impact the biggest ever.) Quantitative Easing (QE) – While it may at first seem counterintuitive, Dr. Hunt explains that excessive money printing (QE) doesn’t cause inflation. It suppresses it by raising debt levels.

Quantitative Easing (QE) – While it may at first seem counterintuitive, Dr. Hunt explains that excessive money printing (QE) doesn’t cause inflation. It suppresses it by raising debt levels.

He notes that the rate at which money circulates through an economy, referred to as the velocity of money, has a far greater impact on inflation than the overall amount of money in the system. This explains why massive amounts of QE haven’t already led to runaway inflation, as many predicted. When QE increased the quantity of money, it led to increased debt levels, and that, in turn, suppressed the velocity of money.

Dr. Hunt believes that today’s record high US and Canadian debt levels have caused record-low money velocity, and that’s also why he doesn’t expect inflation to sustainably accelerate.

Commodity Prices Don’t Drive Inflation – The inflationists have made much of rising commodity prices, but economist David Rosenberg notes that commodity price movements have not historically had a high correlation with inflation. He also argues that the recent surge in commodity prices has been caused by speculative demand “driven by the pandemic money that is burning a hole in investor pockets”, and notes that Chinese demand, which is what typically drives commodity prices, seems to be waning.

Wage Growth Isn’t Actually Accelerating – Rosenberg says that the narrative that US companies are having to raise wages to attract workers isn’t actually borne out by the data. He doesn’t expect wage growth to accelerate against the current backdrop and notes that there are large numbers of part-time workers who want to work full-time, millions more of officially unemployed Americans actively looking for work, and “another 6–7 million [workers who have] left the labor force but say they want a job”. He expects the number of available workers to “grow considerably in the next few months as vaccinations make jobs safer, schools reopen, and enhanced unemployment benefits expire.”

Mauldin notes that while the recent wage increases may end up proving “sticky”, he thinks they are one-offs that are tied to the re-opening and do not signal the start of a trend toward steadily rising labour costs.

Global Inflation Is Still Benign – While US inflationary pressures have risen of late, Mauldin noted that inflation “is still well below ours even in places where COVID-19 had a smaller effect.” He then added: “It is hard to imagine a scenario where the US has significant inflation and the rest of the world doesn’t.”

Price Rises Will Be Transitory – Rosenberg subscribes to the view held by the US Federal Reserve and Bank of Canada (BoC) that the current price rises are “price-level adjustments” that are caused by “by an economy reopening in the face of several supply constraints”.

Technological Advances Will Be Deflationary – Economist Cathie Wood predicts that technology-enabled innovation will continue to drive down prices, but she also predicts that as many as half of the companies in the S&P 500 will be “disintermediated or disrupted” by innovations that will force them to cut prices in order to service their debts.

With both sides of the inflation debate now well argued, let’s relate them back to the question in the title that I promised to take on. How might this information influence your decision to choose a fixed or variable rate against the current backdrop?

While the points explaining the current inflation surge are well made, they are based on short-term data and are underpinned by the belief that fundamental long-term changes are afoot, which will cause inflation to rise to levels that we haven’t seen in several decades, despite the fact that conditions today are markedly different than they were then.

Today, the bond-market consensus believes that we are headed for sustainably higher inflation, and that view is currently baked into the five-year Government of Canada bond yields that our fixed-mortgage rates are priced on. But if inflationary pressures prove transitory, anyone choosing a fixed rate today will have locked in a rate that is based on that higher inflation view for the next five years.

Conversely, the points used to support the view that the current run-up will prove transitory are underpinned by the belief that the short-term data are a result of pandemic-related volatility, and that slow-building longer-term disinflationary forces will still be exerting their impact long after the current dust settles.

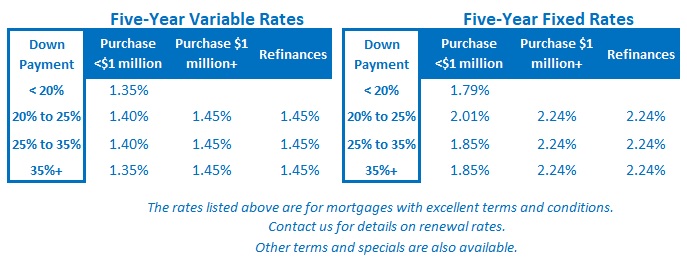

Five-year variable rates are priced on the BoC’s policy rate, and the Bank has so far argued against the bond-market consensus and left its policy rate unchanged. That’s part of the reason why the gap between fixed and variable rates has now widened to about 0.75%, which is the widest it has been in several years.

Simply put, fixed rates are a bet that, this time, inflation will be different, and variable rates are a bet that, over time, inflation will revert back to its recent mean.

For my part, I continue to believe that variable mortgage rates are well worth considering for borrowers who can live with the inherent risk (and worry) that their rate might rise. I think variable rates will stay lower than the consensus predicts, and I also like the increased flexibility they offer, which includes the option to convert to a fixed-rate at anytime and break fees that are capped at only three months’ interest.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed and variable rates held steady last week and remain range bound.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed and variable rates held steady last week and remain range bound.

The latest US and Canadian employment reports will be released this Friday, and I’ll check back next Monday with details from those.