A Busy Year-End Wrap Up

December 20, 2021Is the Bank of Canada About to Start Raising?

January 17, 2022We begin 2022 with Canadian inflation at its highest level since 2003.

Prices have been driven higher by a combination of surging demand, fueled by generous government support payments, and supply shortages tied to the pandemic.

Both the Bank of Canada (BoC) and the US Federal Reserve have been predicting that these factors will have only a transitory impact on inflation.

The term transitory means “non-permanent”, which still appears to be the correct assessment, but it also means “of brief duration”, which hasn’t been the case.

The experience of hotter and stickier inflation has caused both bond-market investors and the wider public to lose confidence in our central bankers.

That is concerning because if people lose faith in their ability to keep inflation contained, they may start accelerating their purchase plans to avoid future price increases, and any such additional increase in demand would push prices still higher. The longer inflation persists, the more likely it becomes that workers will push for higher wages to compensate for their reduced purchasing power. This engenders a self-reinforcing cycle, where the fear of higher inflation causes it to materialize.

With public confidence waning, both the BoC and the Fed had no choice but to stop using the term transitory and to turn more hawkish on monetary-policy tightening. At this point, higher mortgage rates in 2022 appear all but inevitable. But how high will they go?

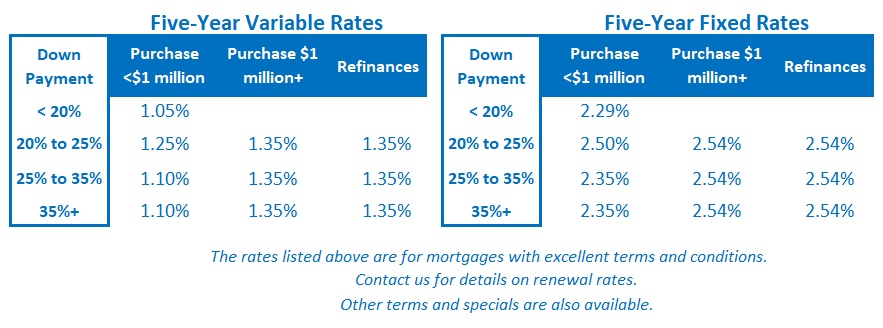

The five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield, which our five-year fixed mortgage rates are priced on, has already surged higher in anticipation of five quarter-point BoC rate hikes in 2022 and two more in 2023. Those are some big moves that are already priced into five-year fixed rates if you lock in today.

Meanwhile, for at least a little while longer, the BoC’s policy rate stands at 0.25%, and that means five-year variable mortgage rates are still available in in the low 1% range, or about 1.25% below their fixed-rate equivalents. That is a much larger buffer than normal.

The futures market is expecting that spread to disappear by the end of the year, but I am skeptical for the following five reasons:

- Omicron’s Impact Is Being Underestimated

In their initial assessment of the Omicron variant, policy makers assumed that its economic impacts would, like its typical symptoms for the vaccinated, be relatively minor.

The Fed initially predicted that Omicron would exacerbate supply shortages and put more pressure on inflation over the short term, but thus far, Fed Chair Powell has said that Omicron will not have much impact on its plans.

I predicted (here) when he made that statement in December that he would regret it, and if he doesn’t already, I expect he will soon. While Omicron’s typical medical impact on the vaccinated has been minor compared to previous COVID variants, it has still caused hospitalizations to spike and is proving quite severe in the unvaccinated.

US vaccination rates and public safety measures have lagged those in Canada and most other developed countries, and that makes the country much more vulnerable to Omicron. If lockdowns are sworn off and US vaccination rates continue to lag, US hospitals may be overrun. That rising risk increases the likelihood that US economic momentum will slow and that the Fed will turn more dovish.

The approach of most Canadian provinces to Omicron has been more cautious. We have closed schools and reinstituted other lockdown restrictions to try to slow infection rates and keep our health-care system from becoming overwhelmed. That reduces our risk of health harm, but it also increases our risk of economic harm, and that, in turn, should turn the BoC more dovish.

- Inflation Will Cool More Rapidly Than the Market Expects

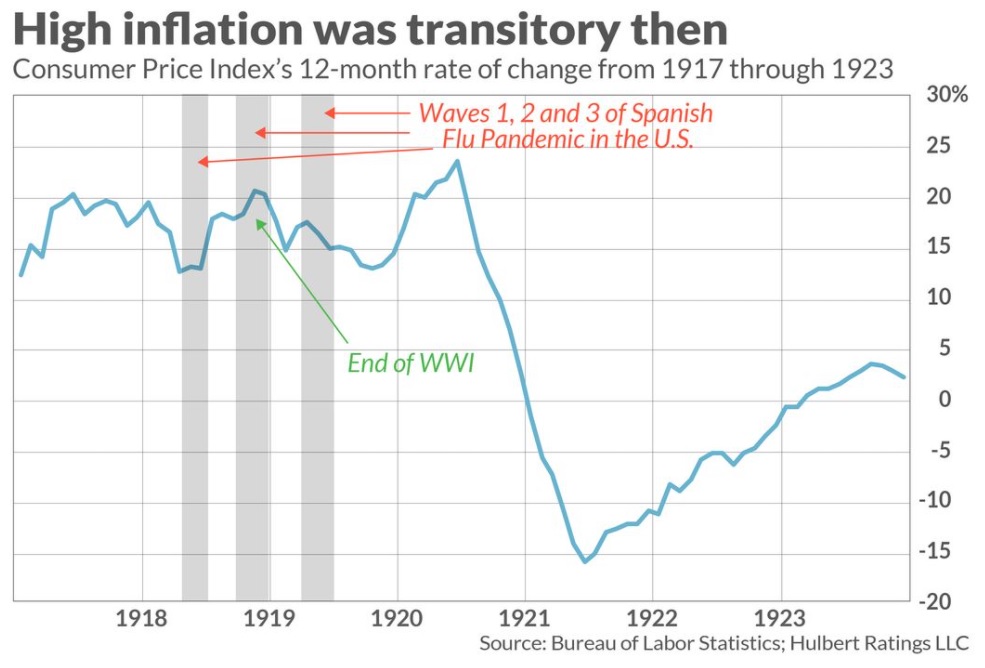

Our Consumer Price Index (CPI) captures price changes over the most recent twelve months.

Prices started to surge in the second half of 2021, and if inflation is going to maintain its current pace into the second half of 2022, it will take another fresh round of price spikes. This seems increasingly unlikely. Supply constraints are gradually being rectified and Omicron has already made consumers more cautious with their spending.

The consensus expects another demand-fueled price spike when we finally free ourselves from the pandemic’s clutches. The theory goes that consumers will spend the cash that they have built up, and that we will see a repeat of the Roaring 20s, when growth and demand surged after the Spanish flu ended.

I have already rebutted that prediction in previous posts. To summarize, the US population was much younger then, US government and household debt levels relative to GDP were miniscule compared to today, and World War I had devastated Europe’s manufacturing capacity, which made the US the world’s dominant exporter over that decade. Very different times.

But what if I’m wrong and we do see a return to the Roaring 20s? Does it follow that inflation will take off?

If past is prologue, the answer is still a firm no.

The chart below shows what happened to inflation when the Spanish Flu ended (and it went on to average less than 2% over the entire 1920s decade).

- There Will Be Much Less Stimulus in 2022

Our policy makers used record levels of fiscal stimulus to offset the pandemic’s initial economic shock.

Those stimuli created many positive short-term impacts that included elevating our GDP, increasing demand, and driving wage growth higher. But those benefits came with a cost. Both US and Canadian budget deficits have soared, driving our government debt levels still higher into the stratosphere.

In addition to being the main contributor to our economic growth in 2021, massive fiscal stimulus was also the primary driver of today’s demand-induced inflationary pressures. But that powerful stimulus has already been sharply reduced on both sides of the 49th parallel, and our governments simply cannot deploy the same largesse to offset any future shocks caused by the pandemic.

The BoC and the Fed are in the same boat as their respective federal governments. They slashed their policy rates to the floor and used quantitative easing (QE), first to flood financial markets with liquidity and then to push bond yields lower. Those moves stimulated financial markets and helped to avoid a repeat of the Great Depression, but they did so by causing asset values to soar, and thereby raising bubble risks across the economy.

Our central bankers now feel compelled to tighten monetary policy to maintain their inflation credibility and help stave off those bubble risks, but that tightening will likely exacerbate, not alleviate, the pandemic’s negative impacts over the year ahead.

If the aggressive rate cuts that have helped asset values surge higher since 2020 are reversed, asset prices would normally reverse direction as well. If that happens, the wealth effect that caused consumers to spend more last year because they were richer (on paper) would also dissipate and cause consumers to turn more cautious.

- The Impact of Rate Hikes Will Be Magnified

Caught between the devil (inflation expectations becoming unanchored) and the deep blue sea (negative economic shocks tied to the pandemic), the BoC and the Fed are reaffirming their commitments to maintain price stability above all else.

But with much less fiscal stimulus buoying economic activity (and exacerbating inflationary pressures), with Omicron’s impacts proving more substantial than first expected, and with elevated debt levels increasing the overall cost of each rate rise, the impact of each hike will be magnified.

All that makes it likely that fewer hikes will ultimately be required to bring inflationary pressures to heel.

If we see anything close to the five BoC rate hikes the consensus is betting on, I think it will prove to be a misstep that will drive our economy into recession. If that happens, rate cuts would almost certainly follow thereafter.

- Labour Costs Will Be Contained

Despite many anecdotes to the contrary, the hard data show that wages are still largely contained in both Canada and the US, even though our employment backdrops are quite different.

In the US, average wages have risen by 4.7% year over year, but they still haven’t kept pace with overall inflation. By the Fed’s own assessment, average wages were suppressed prior to the pandemic, and some of that increase is therefore a catch up. While US employers are still experiencing labour shortages, US workers are expected to return to the labour force now that emergency benefits have expired and they are burning through their built-up cash reserves.

US wages may continue to rise, but so too should the labour-force participation rate as workers start to re-engage out of necessity.

In Canada, our employment recovery has significantly outpaced our overall economic recovery. That’s good for the hiring data but seriously bad for our productivity levels. We are employing more people to do the same amount of work, and that helps explain why our average wages have only increased by 2.9% on a year-over-year basis and why they remain well below their pre-pandemic level with no signs of any imminent breakout.

Now let’s tie all the above commentary back to the key question of whether fixed or variable mortgage rates will prove cheaper in 2022 and over the next five years.

My crystal ball doesn’t come with any guarantees, but with that said, I fundamentally believe the following:

- Omicron’s greater-than-expected impact will make both the BoC and the Fed more dovish.

- Supply challenges will continue to be overcome in the year ahead, and inflation will subside more quickly than expected.

- Demand will moderate without the powerful tailwind of fiscal stimulus.

- The impact of each rate hike will be magnified, and as such, we will need fewer of them.

- Wage growth will not push inflationary pressures materially higher.

Against that backdrop, I expect that variable mortgage rates will save money over their fixed-rate alternatives over the year ahead, and, true to their usual form, are a good bet to do so over the next five years.

It won’t be as easy for variable-rate borrowers this year, because I do expect some rate hikes to ensue, but the gap of about 1.25% over the available five-year fixed rate alternatives provides a large and significant buffer that I don’t think that will close in 2022 as the consensus predicts.

Meanwhile, GoC bond yields have spiked in anticipation of five BoC rate hikes in the year ahead, with two more the year after, and I expect these rates to move lower if and as it becomes clear that the Bank’s raising schedule will be both more gradual and less severe than the consensus forecast. The Bottom Line: US bond yields have recently surged higher in response to the release of the Fed’s minutes from its December meeting, which revealed that it may tighten more quickly than previously forecast. GoC bond yields have risen in sympathy.

The Bottom Line: US bond yields have recently surged higher in response to the release of the Fed’s minutes from its December meeting, which revealed that it may tighten more quickly than previously forecast. GoC bond yields have risen in sympathy.

That said, all the pandemic-related news since then has been worse than expected, and that should soon put an end to the current run up. In the meantime, however, the five-year GoC bond yield has recovered to near its previous high, and if it continues its current trajectory, five-year fixed mortgage rates could move higher over at least the short term.

Five-year variable rate discounts have recently widened a little, and for the reasons outlined above, I don’t expect the BoC to increase at nearly the pace bond-market investors are currently pricing in over the year ahead.