Happy Holidays

December 21, 2020Will Job Losses Hasten the Bank of Canada’s Next Rate Cut?

January 11, 2021We begin 2021 with our glasses half full – and that’s not just because our New Year’s celebrations were cancelled.

On the one hand, recently approved vaccines give us hope that we will beat the pandemic back and return to normal activities sometime this year. But on the other hand, spiking infection rates have necessitated the reintroduction of lockdown restrictions that will severely test our resolve over the near term.

Against that backdrop, and in keeping with my annual tradition, here is my interest-rate forecast for the year ahead.

Let’s start with a quick look at the current consensus forecast.

The majority of market watchers and economists believe that the excess cash that has built up on our personal balance sheets hangs over our economy like a Pinata that will burst open when the pandemic ends. They expect it to trigger a surge in spending that will increase inflationary pressures more quickly than our central bank policy makers are forecasting.

If they’re right, our mortgage rates could move sharply higher. The Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields that our fixed mortgage rates are priced on would be bid up if investors believed that rising inflation would erode their returns.

At the same time, rising inflationary pressures could force the Bank of Canada (BoC) to hike its policy rate, which our variable mortgage rates are priced on, well ahead of its broadcasted 2023 timetable.

At the moment, the consensus forecast resonates with a lot of people.

We all want to believe that a return to normal life is imminent, and we all look forward to our next restaurant visit, haircut and entertainment event. Many Canadians have extra cash burning a hole in their pocket at the moment, and it’s easy to envision demand for some services outstripping their supply over the short term when that cash is deployed.

Borrowers have benefited from record low borrowing rates since COVID began, but not without nervously wondering when they will move higher. Every day I am asked about how much longer today’s rates will last. More broadly, optimistic economic forecasts also appeal to our hope for better days ahead, and who isn’t looking for some extra hope wherever they can find it these days?

The belief that an encore to the roaring 1920s awaits us is widespread – so much so that the contrarian in me is reminded of Rule #9 of Bob Farrell’s 10 Rules for Investing: “When all the experts and forecasts agree – something else is going to happen.”

Bluntly put, I don’t think we have yet hit the bottom in mortgage rates, and barring a short-term run-up, which is always possible, I don’t think they will move sustainably higher this year.

The consensus forecast appears to be based on several flawed assumptions, and it overlooks several key points that lead me to a very different conclusion.

To explain that, let’s look at five key assumptions that I think the consensus has wrong:

- The pandemic will have a definitive end.

No one is going to ring a bell to signal the end of the pandemic. The vaccine rollouts are going to take time, we don’t know how effective they will prove to be, it isn’t clear how many people will voluntarily vaccinate, and we don’t know whether the virus will mutate into new, vaccine-resistant strains (mutations are already evident).

People are going to assess evolving pandemic risks individually, and their decisions to resume activities will happen slowly, over time. I agree with this recent Globe and Mail article, which predicts that the pandemic will end not with a bang, but with a whimper.

- We’re going to return to pre-pandemic “normal”.

The pandemic has changed behaviours in ways that aren’t yet entirely clear, but our economy will need to recalibrate to those changes, which will take time, and the transition will likely be disruptive to our economic momentum.

To cite one example: we all look forward to that first restaurant meal, but what about our second or third one?

I don’t think we’ll collectively go back to eating out as much as we used to. Part of adapting to COVID has been learning to cook for ourselves, and I think that change will permanently reduce our overall propensity to eat out.

New habits, now formed, won’t break easily – and we’ve had a long time to learn new habits.

- There is a lot of free cash that will be deployed over a short period of time.

The pandemic has further widened the gap in our society between the haves and the have-nots.

The haves didn’t see a significant negative impact to their incomes and in many cases took advantage of record low borrowing rates to make large purchases such as real estate, cars, and/or investments in financial markets. Not all of their initially pent-up savings are burning a hole in their pockets anymore.

The have-nots have been receiving government support that in many cases raised their incomes above their pre-pandemic levels. The end of COVID will mean the end of emergency benefits for this group, and they will have less disposable income as a result.

- Spending on services will likely rise, but spending on goods will likely fall.

The end of the pandemic may lead to a surge in spending on services, but some or all of that increase will likely be offset by a drop in spending on goods. In this recent article, economist David Rosenberg noted that “spending growth in the goods sector actually benefited from the pandemic, and the trend this past year doubled the historical norm”. He highlights the risk that demand for goods will drop when the pandemic ends and estimates that “COVID-19-hit services have to rise $4 for every $1 pull-back in the goods sector just to stay even”.

- A consumer spending surge will give our economy a sustainable lift.

Even if we do see a surge in consumer spending, there is no guarantee that it will kick start the broader economy. If it doesn’t fuel a rise in business investment, its economic benefits will be short lived.

When the pandemic is brought to heel, the businesses that made it through will go back to worrying about trade wars, supply-chain disruptions, the lofty Loonie, and the likelihood that their tax rates will soon rise.

The consensus also underestimates the impact that inexorably rising levels of debt in all sectors will have on our post-pandemic outcomes.

Record low rates may have helped stave off a full-blown depression, but they also fuelled eye-watering increases in debt. The more debt an economy has, the more of its income must be used to service it, through larger interest payments, increased taxes, or both. And money spent on interest and taxes is lost to more productive investment that would fuel sustainable growth.

If rates do rise, record-high debt levels will magnify the cost of even a small increase in borrowing rates – and likely kill any rise in inflationary pressures.

Now that I’ve explained why I disagree with the consensus, here’s my take on what’s ahead for our mortgage rates in the year ahead.

Fixed Mortgage Rates

I expect that our fixed mortgage rates will finish 2021 at levels that are either similar to today’s rates or lower.

If COVID infection rates fall dramatically and that leads to the kind of surge in consumer spending that the consensus predicts, we may see inflation rise and fixed rates move up a little over the short term, but I think that any run-ups will be short lived.

Our overall inflation rate is pretty tame at the moment, at least as measured by our Consumer Price Index (CPI), which stands at 1% (well below the BoC’s 2% target). We aren’t likely to see a sustainable rise in inflationary pressures until our output gap comes close to closing. (As a reminder, the output gap measures the gap between our economy’s actual output and its maximum potential output.) Our output gap has widened considerably during the pandemic, and the BoC now expects that it won’t close until sometime in 2023.

Inflation isn’t likely to push our fixed mortgage rates higher, and at the same time, the BoC is actively trying to push them lower. The Bank recently shifted the focus of its aggressive quantitative easing (QE) programs from preserving the liquidity of our financial system to reducing the borrowing rates that most directly impact households and businesses. (Even if it falls short of that goal, at the very least I would expect the Bank to use its QE programs to lean against any short-term run up in the GoC bond yields that our fixed mortgage rates are priced on.)

our fixed mortgage rates are priced on.)

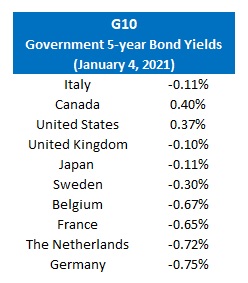

I think there is a reasonable chance that fixed mortgage rates can fall even farther. In addition to my less than rosy economic forecast and the BoC’s QE plans, the bond yields that underpin our fixed mortgage rates will also be impacted by the direction of global bond yields.

To that end, consider that while our five-year GoC bond yields are still slightly positive, at 0.39%, the same can’t be said for the five-year government bond yields in seven of the other G10 countries.

Variable Mortgage Rates

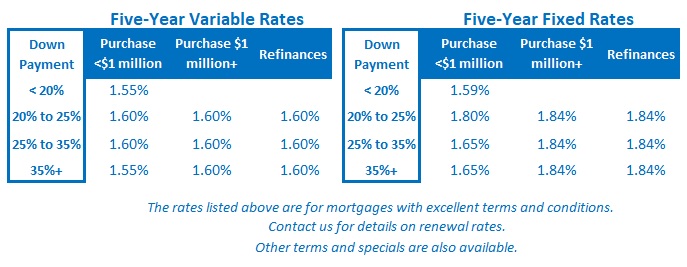

I expect that our variable mortgage rates will also finish 2021 at levels that are either similar to today or somewhat lower.

First a quick reminder: Variable mortgage rates are based on lender prime rates, which move in lockstep with the BoC’s policy rate.

The BoC has made it very clear that it doesn’t expect to raise its policy rate until sometime in 2023. It has also recently floated the idea that it may cut its policy rate a little more, perhaps by another 0.10% to 0.15% in the year ahead if economic conditions worsen. I think any additional rate cut will depend on what happens with the Loonie (for a more detailed explanation of why, check out this post).

If the BoC either holds its policy rate steady or drops it a little more, anyone with an existing variable-rate mortgage will see their rate either stay the same or fall in the year ahead.

The variable rates offered to new borrowers have an additional factor at play. Lenders price their variable mortgage rates using their prime rates and then apply a discount. For example, lender prime rates are 2.45% today, and variable rates are offered at prime minus 0.75% (1.70%) or lower.

If lender discounts widen, the variable rates offered to new borrowers will move lower, even if the BoC holds its policy rate steady. (If those discounts shrink, those same rates will rise instead.)

I expect that aggressive competition among lenders will lead to larger variable-rate discounts, as long as we don’t see COVID-related risk premiums re-appear.

Despite that backdrop, variable-rate borrowers aren’t guaranteed smooth sailing in the year ahead. If fixed mortgage rates do move higher for a period, variable rate borrowers will have their courage tested. In my experience, variable rate borrowers get nervous when the fixed rates they are entitled to convert to, if they locked in, start to rise. If that happens, my advice for those who could still sleep well at night in the current context would be to ride it out.

I will close with a disclaimer.

Predictions are difficult to make at the best of times, and especially now, with all of the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic. I put a lot of time and research into my forecasts, and I think I can reasonably claim to offer an educated opinion, but I don’t have a crystal ball and there are so many factors that influence the direction of rates that any opinion should be taken as just that: an opinion.

The only guarantees in life are of death and taxes. (If we make it through the pandemic, we will have put off the former, but probably in exchange for a lot more of the latter.) The Bottom Line: Based on the detailed analysis provided above, I expect our fixed and variable mortgage rates to either remain at their current levels or move lower in the year ahead.

The Bottom Line: Based on the detailed analysis provided above, I expect our fixed and variable mortgage rates to either remain at their current levels or move lower in the year ahead.