The Bank of Canada’s Rate-Hike Impacts Are Intensifying

September 6, 2022Expect Some Tough Love from the US Federal Reserve This Week

September 19, 2022The Bank of Canada (BoC) raised its policy rate by 0.75% last Wednesday, and that means our variable-rate mortgages and home-equity lines-of-credit will increase by the same amount in short order.

The increase was in line with the consensus forecast, and as such, the Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on held steady.

At least for now.

The consensus forecast also expected the Bank to shift to a more dovish stance in its accompanying policy statement, perhaps by indicating that it would now pause to allow time to observe how its series of sharp increases will impact our economy. That didn’t happen. Instead, the Bank gave no quarter and warned that “the policy interest rate will need to rise further”.

The current gap between the market’s expectations and the BoC’s policy-rate language will need to be resolved one way or the other in the coming months (and the Bank doesn’t sound like it is going to blink this time around).

Here are five more thoughts on the Bank’s latest rate rise and policy statement.

- We’re not done with rate hikes yet.

When the BoC first raised its policy rate from its emergency level of 0.25%, its goal was to get it back up into its neutral-rate range of 2% to 3%. (As a reminder, the neutral-rate range describes the rate level that neither stimulates nor reduces inflation when the economy is operating at full capacity.)

Last week’s 0.75% hike brings the Bank’s policy rate up to 3.25%, and that means it has only now become restrictive to growth, and even then, by the smallest of margins.

While much was made of the fact that our overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) fell from 8.1% to 7.6% last month, overall inflationary pressures are still broadening out below that headline. But our core inflation measures all continued to increase last month, and in her speech last Thursday, BoC Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers noted that “more than half of CPI components grew more than 5% in July”.

It is increasingly clear that the BoC will need to continue pumping the brakes if it is going to stem inflation’s still-rising tide. Up until very recently, most market watchers thought the Bank would pause once it hit 3.25%, but that expectation now appears out of date.

- Future rate hikes will have magnified impacts.

Rate hikes from here on will have increased impact on our mortgage market.

To recap, the BoC’s rate hikes in March, April, and June impacted borrowing costs only. The one in July impacted both costs and borrowing capacities. The one made last week impacted costs and capacities and triggered payment resets on some variable-rate mortgages (which I wrote about in detail in last week’s post).

The same will be true of every additional hike moving forward.

- Recent disappointing economic data aren’t going to stay the Bank’s hand.

There has been a lot made of some recent disappointing economic data, which confirmed that our Q2 GDP growth was lower than expected, that our economy lost another 40,000 jobs in August, and that it has now shed jobs for three months running.

The BoC has conceded that its rapid tightening will cause some level of economic pain but continues to insist that nothing matters more than bringing inflation to heel. (On that note, average wage costs increased from 5.2% to 5.4% last month, despite the accompanying job losses.)

That damn-the-torpedoes approach is risky because it takes about two years for the tightening impacts of rate hikes to exert their full bite – and that’s why central banks have a strong tendency to overtighten. Soft landings are understandably elusive when policy makers rely on lagging economic indictors to make moves in the here and now that will impact the economy two years hence.

- Rate hikes aren’t the only form of monetary-policy tightening being implemented right now.

When the BoC and the US Federal Reserve slashed their policy rates to their floors in response to COVID, they also set up powerful quantitative easing (QE) programs to purchase their government’s bonds in the secondary market. This created artificial demand for these bonds, which helped reduce their yields along with the borrowing rates that were priced on them (such as our fixed mortgage rates).

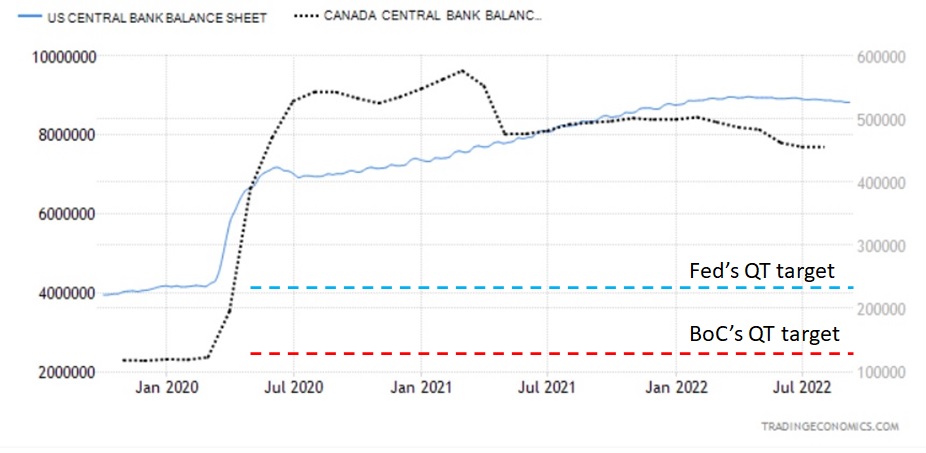

To put that in real numbers, the BoC’s balance sheet increased from about $100 billion to around $500 billion, and the Fed’s balance sheet increased from about $4 trillion to about $9 trillion.

The BoC and the Fed recently announced that they will now begin to allow the bonds they purchased to roll off their balance sheets when they reach maturity, which is referred to as quantitative tightening (QT).

In the BoC’s case, 70% of the GoC bonds on its balance sheet will mature in five years or less, so if it follows through on its plans, there will be an additional $350 billion or so of GoC bonds released into our secondary bond market over the medium-term. For perspective, that surge in supply will equal about 30% of our total federal government debt outstanding. On top of that, over the near term, our federal government will issue another $100 billion worth of new GoC bonds this year to cover its current budget deficit.

For its part, the Fed began reducing its balance sheet by $45 billion per month in June, and it just increased that monthly amount to $95 billion this month. (That matters to Canadians because our GoC bond yields tend to move in virtual lockstep with their US equivalents.) The US federal government also has a budget deficit of roughly $1 trillion in 2022, which it will fund by issuing additional Treasury bonds.

There is ongoing debate about whether the US and Canadian bond markets will be able to absorb such massive infusions of additional bond supply without going tilt, and we may be about to find out who is right on that point.

In the meantime, it’s a safe bet that the current QT programs on both sides of the 49th parallel are going to put significant upward pressure on US and Canadian bond yields for as long as those programs remain in place. Also, if the BoC and the Fed follow through on their currently stated balance-sheet reduction plans, as the chart below shows, QT has a long way to go.

- The BoC needs to front-load more rate hikes now to make up for its earlier policy mistake of staying too low for too long.

The Bank keeps pointing out that it needs to front-load rate hikes now to avoid having to tighten even more severely later, positioning its decision as the responsible thing to do in a tough love sort of way.

However, it should also be noted that part of the reason the Bank can’t pause now at 3.25% is because we are already experiencing the consequences of its earlier delays.

The Bank is justifying the economic pain that is now in store as a way of preventing a policy mistake, but at least some of that pain will be a biproduct of the mistake it already made.

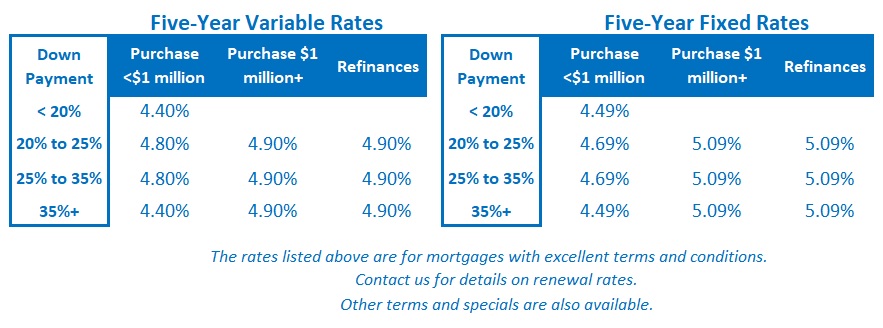

Now let’s turn our focus to see how the BoC’s latest move impacts our current mortgage rates.

As noted in my recent posts, my rate expectations have adjusted in response to changing conditions.

I now think the BoC will have to raise by more than I previously expected, in part to make up for waiting too long before starting to tighten. That could translate to increases of another 0.50% to 1.00% before the Bank finally pauses to allow time for our economy to absorb the impacts of its earlier rate hikes and ongoing QT.

It also seems the Bank is resolved to keeping its economic tourniquet tight even as our levels of pain ratchet up, and that more of it will likely accrue.

At some point, inflation will ease to the Bank’s satisfaction. What’s left of our economic momentum at that point will then need meaningful rate relief to regain its strength. For that reason, while rate cuts are now likely farther off than I previously expected, I still think those cuts have the potential to be significant when they do finally materialize.

If you’re in the market for a mortgage today and don’t want to toss and turn at night worrying about whether the BoC’s policy-rate moves will get inflation back to 2% before your borrowing costs strangle your budget, I think two- or three-year fixed rate options make a lot of sense.

They won’t give you much of a discount today (if any) over five-year fixed rates. They will give you near-term stability while preserving the flexibility to re-negotiate your rate around the time the current inflation surge is likely to be behind us. (In my view, this could take as little as two years but isn’t likely to take longer than three.)

Five-year fixed and variable rates are just about equal now.

Normally that would decrease the appeal of variable rates because there isn’t much (if any) reward offered for taking on floating-rate risk. But we’re in the midst of a significant spike in mortgage rates and today’s five-year variable rates still have the potential to come back down with some meaningful time left on their term when they do. On the other hand, five-year fixed rates don’t offer that potential saving without incurring penalties (which, in many cases, can be prohibitive).

Simply put, if you can stomach today’s heightened uncertainty, I still think variable rates are a responsible bet, but if you prefer stability and a better night’s sleep, I’d recommend the three-year fixed rate as the best way to sleep well while reducing the risk of significantly overpaying at the end of your term. The Bottom Line: The bond market didn’t initially react to the BoC’s more-hawkish-than-expected forecast, but it does seem that both the BoC and the Fed are trying to prepare bond-market investors for more tightening than is currently priced in. While that may take some time to materialize, it portends higher bond yields and fixed mortgage rates ahead.

The Bottom Line: The bond market didn’t initially react to the BoC’s more-hawkish-than-expected forecast, but it does seem that both the BoC and the Fed are trying to prepare bond-market investors for more tightening than is currently priced in. While that may take some time to materialize, it portends higher bond yields and fixed mortgage rates ahead.

Variable-rate borrowers just endured another 0.75% hike last week, and barring any sudden shift in the BoC’s stance, it appears that variable rates will keep heading higher over the near term.