Will the Bank of Canada’s Hawkish Turn Quell Inflation Fears?

November 1, 2021Is It Time for Variable-Rate Borrowers to Lock In?

November 15, 2021 Last week the US Federal Reserve confirmed its plans to begin tapering its quantitative easing (QE) programs and we also received the latest US and Canadian employment data, for October.

Last week the US Federal Reserve confirmed its plans to begin tapering its quantitative easing (QE) programs and we also received the latest US and Canadian employment data, for October.

In this week’s post we’ll provide highlights for each of the items listed above, and I’ll close with a rebuttal to the recent rate-hike hype (which, bluntly put, is getting to be a bit much).

Let’s jump right in.

The Fed Tapers As Expected, But Remains Dovish on Rate Hikes

Last week the US Federal Reserve announced that it will start to reduce its QE purchases by $15 billion each month. At that pace, the Fed will have completely unwound its current QE programs by June of next year, exactly as the market expected, although with the caveat that it will adjust this pace “if warranted by changes in the economic outlook”.

The Fed assessed that “indicators of economic activity and employment have continued to strengthen” but also observed that the recent COVID spike “has slowed their recovery”. It noted that inflation remains elevated, but it remained steadfast in the belief that the run-up has been caused by “factors that are expected to be transitory”.

In his accompanying remarks, Fed Chair Jerome Powell cautioned that the Fed’s decision to taper its QE programs “does not imply any direct signal regarding our interest rate policy”, and he reiterated the Fed’s commitment to use “a different and more stringent test” to determine when rate hikes will be appropriate.

That guidance was more dovish than expected, and the futures market reduced its bet on the number of Fed rate hikes next year from 2.5 to less than 2, and also adjusted its bet on the number of Bank of Canada (BoC) rate hikes in 2022 from 4 down to 3.5. (I will still take the under on that bet.)

If past is prologue, the Fed’s tapering announcement, somewhat surprisingly, portends a drop in bond yields going forward.

That may not sound intuitive, because the Fed will be withdrawing support for the bond market and that would be expected to cause yields to rise. But financial markets have already driven up yields to price that in prior to last week’s announcement.

After they buy the rumour, markets are known to sell the fact.

On that note, the chart below from Bloomberg via the Edward Jones Weekly market wrap, shows what happened to US bond yields during the Fed’s last QE tapering period in 2014. If the same happens this time around, we’ve already seen the near-term top in bond yields, and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them.

If the same happens this time around, we’ve already seen the near-term top in bond yields, and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them.

US Employment Data Rebounds As Emergency Benefits Run Out

The US labour market is stuck in an unusual jam at the moment.

It has more job openings than there are unemployed workers to fill them, but despite that, the pace of hiring has been slower than expected.

This disconnect has been attributed, in part, to the fact that the US federal government has been providing generous emergency unemployment benefits which have allowed workers to remain on the sidelines. Those benefits ended in September, and, perhaps not coincidentally, US employment surged higher by 531,000, higher than the consensus estimate of 450,000.

The unemployment rate fell from 4.8% to 4.6%, with the largest gains coming from the leisure and hospitality sector, which added 164,000 new jobs.

Average wages increased by 0.4% last month and have now risen by 4.9% on a year-over-year basis.

The recent run-up in wages has raised concerns that labour costs will cause inflation to spiral. For its part, the Fed does not share that belief. In his press conference commentary last week, Fed Chair Powell noted that wage increases had been running below inflation for some time prior to the pandemic and that some catch-up was needed. He added “at this point we don’t see troubling increases in wages, and we don’t expect those to emerge, but will be watching carefully”.

Last month’s headline result was encouraging, but the US employment recovery is still a work in progress. For some broader perspective:

- The US economy is still more than 4 million jobs short of its pre-pandemic employment rate.

- The US participation rate, which measure the percentage of working-age Americans who are either working or actively looking for work, stands at 61.6%, or 1.7% below where it was pre-pandemic.

- There are 1.2 million more Americans classified as long-term unemployed than there were in February of last year.

- Last month there were an estimated 6 million Americans who were not currently counted in the labour force, but who wanted a job. That number stood at 968,000 last February.

The outlook for the future of the US jobs recovery is still uncertain, especially considering that US GDP growth, which averaged 6.5% on an annualized basis over the first half of this year, slowed to only 2% in the third quarter.

Canadian Employment Data Loses Some Shine

The Canadian economy faces its own employment challenge.

In September, we reached the point where we had recovered (or replaced) all of the jobs that were initially lost to the pandemic, but that milestone came with an important caveat. Our GDP growth is still well below its pre-pandemic level, and that means that our employment recovery is outpacing our overall economic recovery.

That has happened, in part, because our federal government’s emergency support payments to businesses were specifically aimed at keeping workers at least marginally attached to their employers. Those payments were stopped last month, and it is not yet clear whether those marginally-attached jobs will be retained.

Statistics Canada is estimating that our GDP growth will come in around 2% in the third quarter, which isn’t the kind of robust growth that our policy makers had in mind, and not what most economists were expecting for an economy that has received such massive stimulus injections.

Against that backdrop, our economy added 31,000 new jobs last month. While not a bad headline result, that number fell short of the consensus forecast and was well below the 157,000 jobs that were added in September.

The biggest gains came in the retail sector, which added 72,000 positions last month, and the most notable losses came in accommodations and food services, which shed 27,000 jobs.

Our unemployment rate fell from 6.9% to 6.7%, but Statistics Canada noted that that number rises to 8.7% if we add Canadians who wanted a job but weren’t actively looking for one.

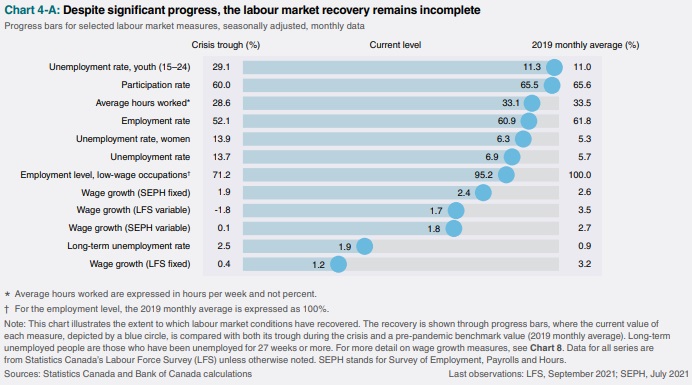

The BoC included an excellent dashboard summary of our current labour-market conditions (see chart) in its latest Monetary Policy Report. It shows that our employment recovery still has a long way to go, and provides a convincing rebuttal to claims that our labour costs are at risk of spiralling out of control. A Grain of Salt For Rate Hike Expectations

A Grain of Salt For Rate Hike Expectations

The consensus narrative continues to warn that mortgage borrowers should lock in a fixed rate before variable rates skyrocket next year.

At one point the bond futures market was pricing in six quarter-point BoC rate hikes in 2022 and prominent economists and market commentators kept one-upping each other with their predictions of impending doom.

(Scotiabank economist Derek Holt won the first prize when he recently predicted that the BoC will hike “four times in the second half of next year, and four more times in 2023.”)

At a time like this, I am reminded of one of Bob Ferrell’s ten rules for investing: “When all the experts and forecasts agree, something else is going to happen”.

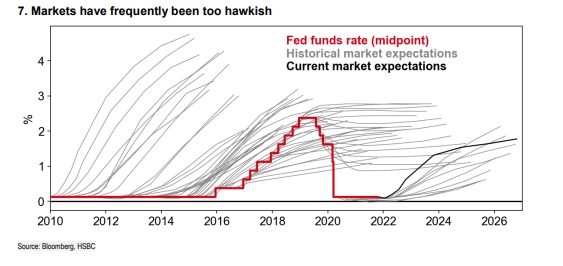

On that note, the chart below, courtesy of Manulife Chief Economist Frances Donald, is the picture that, on this topic, speaks a thousand words. It shows how market expectations of Fed rate hikes have compared to the Fed’s actual hikes. Human nature being what it is, I am confident that a similar comparison of actual vs. expectations for the BoC’s policy rate going forward will look very similar.

Human nature being what it is, I am confident that a similar comparison of actual vs. expectations for the BoC’s policy rate going forward will look very similar.

On that note, last week the market has already reduced its bet on BoC rate hikes in 2022 from 6 to roughly 3.5.

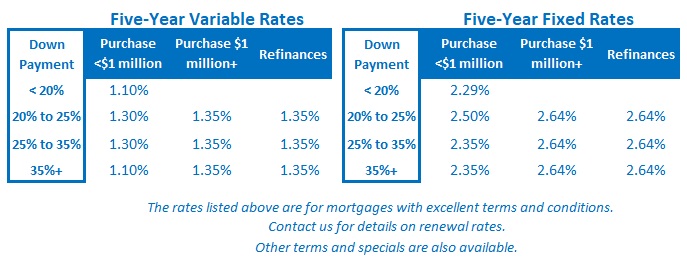

Bond-market investors are a volatile bunch, central bankers less so. The Bottom Line: We saw another round of five-year fixed rate increases last week, and they have now risen a total of between 0.50% and 0.60% in short order. That said, tapering has now been fully priced in, and that should be it for now. I think the next catalyst for a move in Government of Canada bond yields, and, by association, our fixed mortgage rates, will be disappointing GDP data at the end of the month.

The Bottom Line: We saw another round of five-year fixed rate increases last week, and they have now risen a total of between 0.50% and 0.60% in short order. That said, tapering has now been fully priced in, and that should be it for now. I think the next catalyst for a move in Government of Canada bond yields, and, by association, our fixed mortgage rates, will be disappointing GDP data at the end of the month.

Five-year variable rate mortgage discounts widened again last week, and the market also priced in a less aggressive BoC rate-hike timetable after the Fed remained dovish on its timing (along with both the European Central Bank and the Bank of England).

For my part, I continue to believe that variable rates will stay lower for longer than today’s headlines predict. The mainstream analysis continues to make the case for fixed rates, but a deeper dive based on the balance of probabilities still favors variable rates at their heavily discounted levels.