The US Fed Maintains Its Slow-and-Steady Approach

August 30, 2021Federal Election Primer: Mortgage-Specific Proposals

September 13, 2021The Bank of Canada (BoC) will be in a tough spot when it meets this week.

Normally it would try to hold steady in the middle of a federal election so that its words and actions aren’t seen to be favouring one party over another. But normal left town when the pandemic arrived and hasn’t been seen since.

The BoC will have to acknowledge our latest GDP data, which confirmed that our economy is on shakier footing than it previously believed, and more broadly, that we face a tougher road ahead.

At its last policy-rate meeting, in July, the BoC assessed our economy as “impressively resilient” and predicted that growth would “rebound strongly” and be “more durable” after lockdown restrictions were lifted.

In its accompanying Monetary Policy Report (MPR), the BoC forecast that our GDP growth would rise by 6% in 2021, recovering most of our pandemic losses over that span, but the latest data make that estimate appear wildly optimistic.

Our GDP declined by 1.1% in Q2 on an annualized basis, well below the BoC’s forecast 2% growth. It fell by another 0.4% in July, and that portends a disappointing result in Q3 as well.

So, what has changed?

In April, when the BoC moved up the expected timing of its next policy-rate hike to “some time in the second half of 2022”, it did so in large part based on the expectation that a robust US recovery would ensue.

The Bank predicted that “a rapid rollout of [US] vaccines and substantial [US] fiscal stimulus” would create “spillover benefits to Canada through higher demand for exports and stronger commodity prices”. It expected strong growth in foreign demand to trigger a rebound in exports that would help fuel a more broad-based recovery.

Since then, US vaccination rates have stalled out, US infection rates are spiking back up to near record highs, and as US stimulus programs have wound down, so too has US economic momentum. Last week’s US employment report provided the latest evidence. It showed a gain of only 235,000 new jobs in July, well short of the consensus forecast of 730,000.

Against that backdrop, it’s not surprising that the export-led recovery that the BoC expected hasn’t materialized, and that our export sales fell by 15% in Q2.

The Bank’s prediction that our recovery would be carried along by a robust recovery in the US isn’t the only assumption that needs to be recalibrated.

The economic scarring caused by our third-wave lockdowns is also likely to be more severe than initially estimated.

At one point, the prevailing wisdom was that the negative impacts from each successive lockdown would be diminished because by this point businesses have figured out how to manage through them. But the latest GDP data indicate that the longer the pandemic drags on, the more severe the economic damage will be (and the longer it will take to recover).

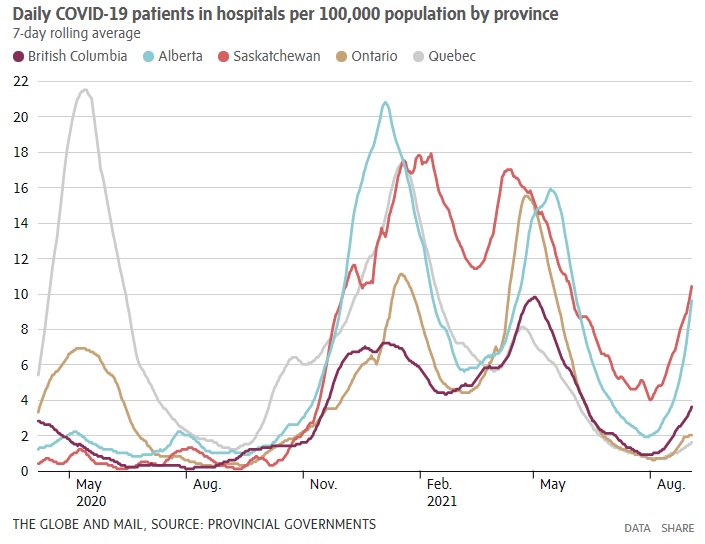

While we’re on the topic of lockdowns, our public health experts are warning that slowing vaccination rates and relaxed public health measures are greatly increasing the risk that the highly contagious COVID variants will trigger a fourth wave. (It’s already occurring in Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, as per the chart below.)

If those forces weren’t concerning enough (and I know this is the last thing anyone wants to be reminded of), our weather is about to turn from a tailwind that supported our recovery to a headwind that inhibits it. As we start congregating more indoors, infection rates will almost certainly rise.

If those forces weren’t concerning enough (and I know this is the last thing anyone wants to be reminded of), our weather is about to turn from a tailwind that supported our recovery to a headwind that inhibits it. As we start congregating more indoors, infection rates will almost certainly rise.

Which brings me to the final elephant in this crowded room.

Our kids are also about to return to school, and the next stage of our recovery will be determined largely by whether they can safely remain there. (Here’s hoping.)

While the BoC can be forgiven for consistently erring on the optimistic side, not acknowledging our deteriorating data and rising risks would be willful blindness.

Simply put, this Wednesday the Bank should predict tougher sledding ahead and extend its rate-hike guidance beyond “some time in 2022”.

(At the very least, this recalibrated assessment would likely help remove the premium that has been sticking to the Loonie since the BoC moved up its rate-hike timetable and the Fed didn’t.)

This won’t be an easy decision for the BoC.

If it assesses that our economic backdrop is deteriorating, that will hurt the public’s perception of how well our federal government has managed the pandemic. And if the Bank waits until after the September election in, it can use its next MPR to provide a detailed justification for its altered outlook in October.

But when the situation on the ground changes considerably, as it clearly has, correct policy should matter more than political considerations.

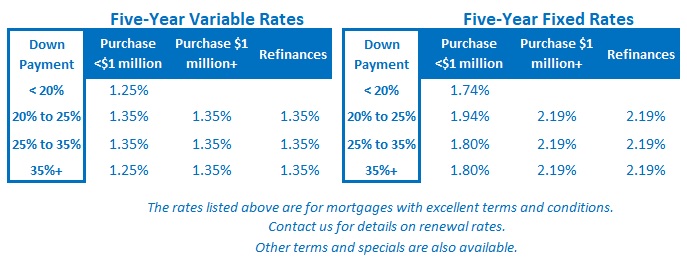

If the BoC doesn’t recognize that, then the greatest loss will be its credibility. The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to inch down last week, and I expect that trend to continue over the near term.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to inch down last week, and I expect that trend to continue over the near term.

Five-year variable rates held steady. Discounts off prime are near their widest-ever levels, so I don’t expect variable rates to go down much from here. That said, I still think the BoC will push out the timing of its next rate hike soon. I think it should do that this Wednesday, even though there will be pressure to hold off until its meeting in October.