The Current Case for Variable-Rate Mortgages

August 23, 2021The Bank of Canada’s Tough Spot

September 7, 2021 Last Friday US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell delivered his much-anticipated speech at the Jackson Hole symposium, an annual global conference for central bankers, finance ministers, academics, and prominent investors.

Last Friday US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell delivered his much-anticipated speech at the Jackson Hole symposium, an annual global conference for central bankers, finance ministers, academics, and prominent investors.

In the lead up, the market consensus predicted (again) that rising inflationary pressures would compel Powell to signal a more hawkish Fed shift, and US bond yields rose in anticipation.

Powell acknowledged that the recent run-up in US inflation had been more intense and persistent than expected, but he qualified that observation with a detailed review of why the Fed continues to believe those pressures will dissipate. He also recommitted the Fed to its slow-and-steady approach, and US bond yields fell immediately afterwards.

If you’re keeping an eye on Canadian mortgage rates, Powell’s commentary is worth a quick review.

The Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields, which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on, move in near lockstep with their US equivalents. And the Bank of Canada (BoC) is unlikely to raise its policy rate, which our variable mortgage rates are priced on, ahead of the Fed because that would cause the Loonie to spike against the Greenback and hammer our export sector.

At the moment, the Fed is using a combination of quantitative easing (QE) and a rock-bottom policy rate to stimulate the US economy.

It conducts QE by purchasing long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. This extra (artificial) demand helps to drive their prices up and their yields down, and that translates to lower borrowing costs for businesses and households.

Right now, the Fed is using QE to purchase a total of $120 billion worth of US debt each month. As the US economic recovery strengthens, the Fed will begin to reduce or taper these purchases. The withdrawal of that demand should then cause US bond yields (and their Canadian equivalents) to rise, along with the cost of other debt that is priced on those bond yields (such as fixed our mortgage rates).

Sometime after it begins to taper, the Fed will begin to raise its policy rate. Crucially, though, in his speech last week Fed Chair Powell made it clear that the decisions around QE tapering and policy-rate rises are not directly linked and that tapering should not be interpreted “as a direct signal” that the Fed is about to start hiking rates.

Furthermore, while Powell acknowledged that the US economy is nearing the point where it may be appropriate for the Fed to begin reducing its QE purchases, he also made it clear that it would use “a different and substantially more stringent test” to determine when rate hikes will be appropriate.

From a Canadian mortgage perspective, while Fed tapering could impact GoC bond yields and our fixed-mortgage rates in the months ahead, it still sounds as though any Fed rate hikes that could impact the timing of future BoC rate hikes, are still a long way off.

Here are some other noteworthy highlights from Powell’s speech:

COVID and the recovery

Powell noted “a strong employment report for July, but also the further spread of the Delta variant”.

Spiking US infection rates and a surprisingly high number of vaccine-hesitant Americans cast doubt on the prospects for continued US employment strength, especially if these “evolving risks” force school closures and necessitate additional lockdown measures.

Progress towards the Fed’s dual mandate

The Fed is charged with using its monetary policy to achieve a dual mandate:

- Maximum employment, which is defined as the highest level of employment that can be achieved while keeping inflation stable

- Stable prices, which is defined as maintaining a target inflation rate of 2%. (The Fed recently modified this portion of its mandate to achieving an average inflation target of 2% over the longer term to allow room for inflation to temporarily overshoot following an extended period below target.)

Powell assessed that the US economy still has “much ground to cover to reach maximum US employment”, and while he observed that “inflation has reached 2% and is on track to moderately exceed 2% for some time”, he also cautioned that “time will tell whether we have reached 2% inflation on a sustainable basis”.

The inflation debate

Powell reiterated the Fed’s belief that the current run-up in US inflation will prove transitory. He offered five key observations in support of that assessment:

- The current inflation run-up “is so far largely the product of a relatively narrow group of goods and services that have been directly affected by the pandemic and the reopening of the economy”. The Fed expects those prices to normalize as supply/demand imbalances are rectified.

- There is already evidence of this happening. (Used cars and lumber prices are good examples.)

- Labour costs haven’t taken off. Inflation isn’t likely to rise sustainably if labour costs are largely contained, which they have been thus far. When inflation took off in the 1970s, the primary driver was a wage-price spiral, and the Fed doesn’t see evidence of that now.

- Longer-term inflation expectations are stable. Fears about higher inflation could cause consumers to accelerate purchases, and that, in turn, could drive up prices in a self-fulfilling prophecy. But thus far, consumer surveys show long-term inflation expectations hovering around 2%, and that’s consistent with the Fed’s outlook.

- Longer-term disinflationary forces haven’t gone away. Pandemic distortions aside, Powell notes that “there is little reason to think” that the factors that exert downward pressure on prices such as globalization, aging demographics, and technological advances “have suddenly reversed or abated”. He predicted that these factors “will continue to weigh on inflation as the pandemic passes into history.”

The market consensus is still trying to rewrite the Fed’s narrative, but it hasn’t yet succeeded.

While Powell made it clear that the Fed will be ready to reduce monetary-policy stimuli when the US recovery reaches a sustainable footing, he reconfirmed its slow-and steady approach and, importantly, set QE tapering and policy-rate hikes on distinctly different trajectories. The Bottom Line: US Treasury yields rose steadily last week in the lead-up to Fed Chair Powell’s speech on Friday (and the five-year GoC bond yield rose in sympathy with its US equivalent). Both retraced that rise once it became clear that Powell and the Fed would maintain their slow-and-steady approach.

The Bottom Line: US Treasury yields rose steadily last week in the lead-up to Fed Chair Powell’s speech on Friday (and the five-year GoC bond yield rose in sympathy with its US equivalent). Both retraced that rise once it became clear that Powell and the Fed would maintain their slow-and-steady approach.

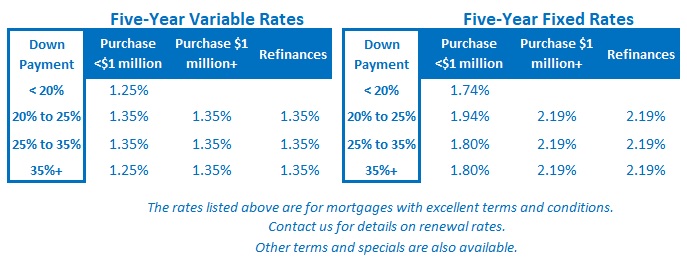

Five-year fixed rates continued to inch down last week, and I expect that trend to continue over the short-term. Five-year variable rates held steady, and there is no current reason to expect that to change anytime soon.