Employment Growth Surges, But So Do US Infection Rates

August 9, 2021The Current Case for Variable-Rate Mortgages

August 23, 2021The Bank of Canada (BoC) and the US Federal Reserve plan/hope to keep their quantitative easing (QE) taps open and their policy rates nailed to the floor until their respective economies have fully recovered from their pandemic shocks.

But inflation could be the fly in their ointment.

If it proves to be persistent, the BoC and the Fed may be forced to start tightening their monetary policies sooner than they would ideally prefer.

A few months ago, the market consensus was betting heavily on that outcome as inflationary pressures started to build.

Prices that plunged at the outset of the pandemic were normalizing back to their pre-pandemic levels, shortages and bottlenecks were raising costs, and, as lockdowns ended and elements of normal life resumed, demand was recovering much more quickly than supply. We have also been experiencing an epic drought, which is causing food prices to spike (although it doesn’t get much mention).

As these transitory impacts ease, some market watchers warn that longer-term pressures will build in response to massive new government spending initiatives (such as the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill that was passed by the US Senate last week) and the release of the huge piles of excess cash sitting on household balance sheets.

But there are also reasons to believe that inflation won’t run as hot as feared.

The surge in demand that we saw as lockdowns lifted will likely level off, and, over the longer term, some demand destruction is expected as consumers reduce purchases in response to higher prices and forgo activities such as dining out, due to lingering COVID fears. If demand wanes, so too will some inflationary pressure.

Thus far, our recent inflation spike is the result of significant price rises in a small subset of categories rather than broader across-the-board increases, which would likely be longer lasting. On that note, economist David Rosenberg observed last week that in July “14% of the [US] core CPI has an inflation rate of over 20%, and the other 86% has an inflation rate of just over 1%”.

At the same time, while recent government spending announcements include significant sums, it will take years before most of that spending will occur (and impact inflation).

Most importantly, the excess cash sitting on household balance sheets is concentrated in more affluent households, which are more likely to save that money than spend it, and if it isn’t circulating through the economy, it isn’t going to raise inflationary pressures.

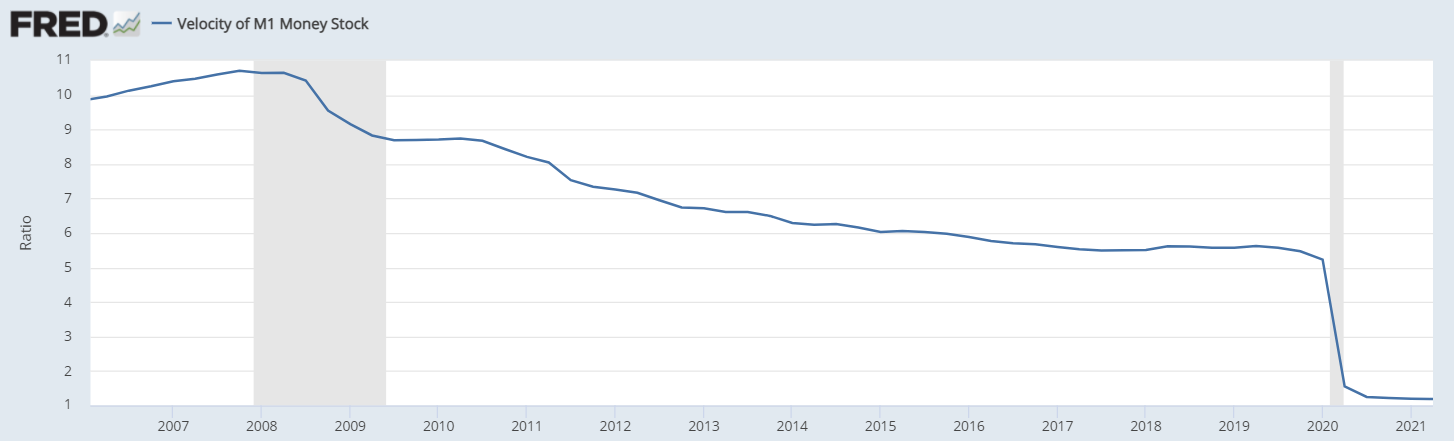

If you have been wondering why the combination of low policy rates, eye-watering QE from the Fed, and generous emergency-benefit payments from the US federal government haven’t sent US inflation to the moon yet, the chart below provides the missing link.

It shows the rate at which M1, which is the supply of US money, has been circulating through the US economy, referred to as the velocity of money. Note that it has fallen steadily since the Great Recession in 2008 and sharply since the start of the pandemic.

Finally, while inflationary pressures have risen sharply in North America, they remain mostly benign elsewhere in the world, and that should produce a moderating effect as global trade recovers.

Now let’s check on the latest US inflation data, which were released last week:

- The US Consumer Price Index (CPI) for July held steady at 5.4% on a year-over-year basis, remaining at its highest level in more than a decade.

- That said, the rise in US CPI slowed sharply on a month-over-month basis, from 0.9% in June to 0.5% in July.

- US core CPI, which strips out the volatile food and energy components, eased back from 4.5% year-over-year in June to 4.3% in July.

- US core CPI decelerated on a more pronounced basis month-over-month, from 0.9% in June to 0.3% in July.

While the latest data confirm that US inflation is still running hot, they also imply that overall price pressures may have peaked.

US bond-market investors appeared to draw the same conclusion because US Treasury yields fell last Wednesday after the July data were released. That’s good news for anyone keeping an eye on Canadian mortgage rates because Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields, which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on, tend to move in lockstep with their US equivalents.

US Fed Chair Powell recently acknowledged that US inflation risks remain tilted to the upside over the near term, but last month’s CPI data came in largely as expected and aren’t likely to cause a material shift in the Fed’s current outlook, which is ballparking its next policy-rate rise around two years hence.

As a reminder, I continue to believe that the BoC won’t raise its policy rate, which our variable mortgage rates are prices on, much ahead of the Fed (if at all) – and despite the fact that the BoC is currently forecasting its next rate hike in the second half of next year.

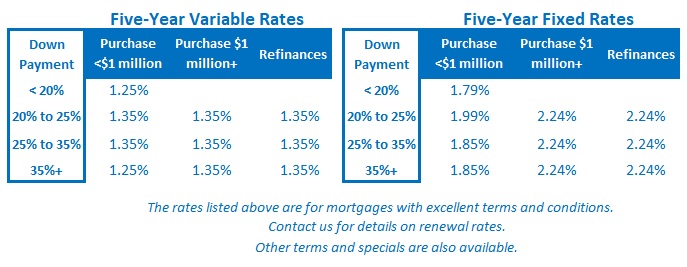

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed and variable rates held steady last week.

While the belief/worry that rate rises are imminent is still prevalent among mortgage borrowers, our five-year GoC bond yield continued to fall last week, and if that trend continues, the next move in the five-year fixed rate will be down, not up.