Why the US Employment Data Are Key for Canadian Mortgage Rates

July 5, 2021My Take on the Bank of Canada’s Latest Forecasts

July 19, 2021 Last week Statistics Canada confirmed that our economy added an estimated 231,000 new jobs in June, which was higher than the consensus forecast of 195,000.

Last week Statistics Canada confirmed that our economy added an estimated 231,000 new jobs in June, which was higher than the consensus forecast of 195,000.

In normal times that type of job growth would have sent Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields soaring as investors priced in rising inflation risks and future Bank of Canada (BoC) rate hikes, but this time around, bond-market investors met our latest employment headline with a shrug.

A quick look at the composition of last month’s job growth makes it clear why:

- All the gains came from part-time jobs (+264,000). We shed another 33,000 full-time jobs in June, adding to the 143,000 that we lost in April and May, and self-employment also dropped by 63,000.

- Last month’s gain of 231,000 jobs was less than the 275,000 that we lost in April and May, so we’re not even back to where we were in the first quarter.

- Most of the gains (+164,000) were for youth aged 15 to 24, and the newly created jobs were centred in accommodations and food services (+101,000), and retail (+75,000). The bond market isn’t going to get too excited about young people getting hired for summer jobs and part-time workers who were impacted by lockdowns getting re-hired.

- The quality of our employment mix suffered in other ways as well. Our economy lost 48,000 goods-producing jobs last month and increased the total second quarter losses for that sector to 108,000. Goods-producing jobs tend to be higher paying, as are those in construction (-23,000 in June) and natural resources (-9,800 in June).

- Most encouragingly, the number of employed Canadians who worked less than half of their normal hours (referred to as “underemployed” workers) decreased by 276,000, which is a sign that businesses are ramping up and workers are returning to more normal conditions.

There is always some level of noise in the monthly employment data but even more so during the pandemic when gains and losses are magnified by shutdowns and re-openings.

The most useful information helps us gauge how our labour market is faring relative to its pre-pandemic levels. Here is an update using that lens:

- Total employment is still down 340,000 compared to February of 2020, and our working-age population has since grown by another 200,000 workers. That means our economy still needs to add 540,000 new jobs to fully re-establish its pre-pandemic employment rate.

- Our unemployment fell from 8.2% to 7.8% last month, but it was 7.5% at the outset of the pandemic.

- Full-time employment is 330,000 jobs below its pre-pandemic level, self-employment is still 200,000 jobs short, but thanks to last month, part-time employment has now almost fully recovered.

- Our participation rate, which measures the total percentage of working-age Canadians who are either working or actively looking for work, has bounced back to 65.2%, which is near its pre-pandemic level. That said, our long-term unemployment cohort is still 300,000 workers above its pre-pandemic level, so the remaining gap in our participation rate will be increasingly difficult to close.

- Here are Stats Can’s latest estimates of where all categories of underutilized workers stand relative to their pre-pandemic levels:

- Unemployed workers: +340,000

- Employed but working less than half of normal hours: +341,000

- Temporarily laid off (but planning on returning to work soon): +99,000

- Wanting to work but not currently looking: +120,000

- Unemployed core working-age Canadians (aged 25 to 54): +162,000

In conclusion, while last month’s employment headline was encouraging, a closer look at our employment data confirms that our labour-market recovery is still only in the middle innings.

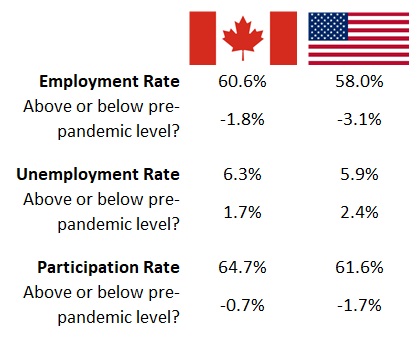

Now let’s check in on how we are faring relative to the US labour market (with Stats Can’s data adjusted to align with US methodologies): The data in the chart confirm that our employment recovery is farther along than the US and help to explain why the BoC is forecasting that it will start raising its policy rate in the second half of 2022, whereas the US Federal Reserve isn’t forecasting a raise until 2023.

The data in the chart confirm that our employment recovery is farther along than the US and help to explain why the BoC is forecasting that it will start raising its policy rate in the second half of 2022, whereas the US Federal Reserve isn’t forecasting a raise until 2023.

For my part, I continue to believe that the BoC is unlikely to raise ahead of the Fed, and that our economy’s heaviest lifting lies ahead (and that’s true even if the rapidly spreading Delta variant and vaccine hesitancy don’t conspire to force us back into lockdown in the months ahead). The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed and variable mortgage rates held steady again last week.

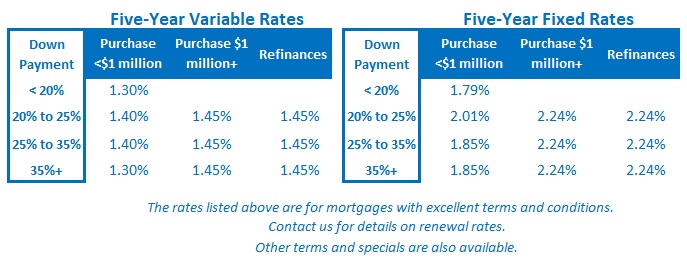

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed and variable mortgage rates held steady again last week.

The bond market’s collective shrug in response to our latest employment report suggests that it will maintain a wait-and-see approach for now. I expect the BoC to do the same when it meets this Wednesday, and I’ll check back next week to confirm whether that was the case.