Why the Bank of Canada Won’t Hike Before the US Fed

May 3, 2021US Inflation Spikes to Its Highest Level in More Than a Decade

May 17, 2021Last week’s employment data came in worse than expected on both sides of the 49th parallel, casting doubt on the market consensus narrative that labour costs, and, by association, overall inflation, will rise more quickly than both the Bank of Canada (BoC) and the US Federal Reserve are forecasting.

The Canadian economy shed 207,000 jobs last month.

Losses were expected after the reintroduction of lockdowns across the country, but the total came in higher than the consensus forecast of 175,000. Our economy has thus far shown surprising resilience coming out of lockdowns, but the more of them we have and the longer they last, the greater the odds that more permanent economic scarring will occur.

The US headline was the bigger story.

The US employment recovery was expected to accelerate in April in response to impressive vaccination rates and huge injections of federal government stimulus, with the consensus forecasting 1 million new jobs. In the end, only 266,000 new jobs materialized, and the original estimate of +916,000 jobs in March was also revised down to +770,000.

The US employment data will likely impact Canadian mortgage rates more than our own data over the short and medium term, as I explained in last week’s post.

To quickly recap, I argued that the BoC wouldn’t raise before the Fed, because that would cause the Loonie to soar higher against the Greenback, and in so doing, short-circuit the export-led recovery the Bank is counting on.

The Fed continues to estimate that it won’t hike its policy rate until sometime in 2024, and if that sounds way off the mark, consider that while the BoC has a singular mandate to keep inflation “low, stable and predictable”, the Fed operates under a dual mandate. In addition to keeping prices stable, the Fed is also charged with fostering “maximum employment”.

US Fed Chair Jerome Powell recently explained that, in the current context, fostering maximum employment means keeping the Fed’s policy rate at 0% until the employment recovery is “complete”. A closer look at the US employment data helps explain why the Fed believes that it is still “a long way” from that goal:

- The US economy must add 8 million more jobs to recover all of those lost to the pandemic, and it will need to add another 2 million jobs on top of that to account for the natural expansion of its labour force over the interim period.

- The US unemployment rate now stands at 6.1%, still well above the pre-pandemic rate of 3.5% that is needed to meet the Fed’s definition of a complete recovery.

- Interestingly, and this is a point the consensus has yet to reconcile, even when US unemployment did reach 3.5% in the past, US labour costs were still largely contained. Back then, the consensus also predicted that a combination of labour shortages and skills mismatches would push up labour costs and cause inflation to run hot. But neither happened.

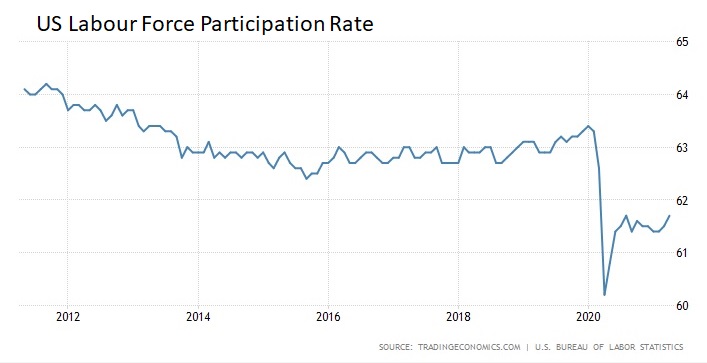

- The US economy’s participation rate, which is a broader measure of employment that captures the percentage of all adult Americans who are currently working, is also well below pre-pandemic levels (see chart below). This is in part because US schools and daycares have yet to fully reopen, and that is forcing some parents to stay home to look after their children, but it also reflects a rising number of workers who have been unemployed for an extended period and will take longer to re-engage.

- In his most recent press conference, Fed Chair Powell predicted that the US employment recovery would take longer than the consensus expects, in part because companies have been telling the Fed that they are focusing on “better technology and perhaps fewer people”. If that’s true, and if changes in consumer behaviours also impact the employment landscape, it will take the US economy longer to invent new jobs than it would otherwise take to restaff old ones.

While we don’t want to make too much of one month’s employment data, April was supposed to be a big month for US employment and the results confounded market watchers and appeared to contradict the consensus narrative. Score one for the Fed (and the BoC).

If you will indulge me, I will close today’s post on a personal note.

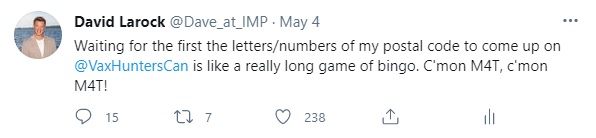

As previously mentioned, I had pledged to take the first vaccine offered to me, but procuring one proved to be a frustrating process.

I signed up for waiting lists with Shopper’s Drug Mart, Rexall, and Costco, and I started following @vaxhunterscan on Twitter (which is a fantastic account that gives real-time updates on availability in your area). Friends also emailed me leads on pop-up locations that had expiring doses and were issuing open calls, but I worried they would run out before I could get there.

My wait eventually prompted the tweet below: Then on Friday night I received a text from a Shopper’s Drug Mart in Mississauga offering me an appointment. I took the first time available and drove there yesterday morning to receive my jab.

Then on Friday night I received a text from a Shopper’s Drug Mart in Mississauga offering me an appointment. I took the first time available and drove there yesterday morning to receive my jab.

While it took a long time for my opportunity to arrive, when it finally did, the process was easy and efficient.

I am relieved to know that while the pandemic is by no means over, I have dramatically reduced my personal health risks, and I am happy to now count myself among the herd that our country is depending on to end this crisis once and for all. The Bottom Line: Last week’s disappointing employment data helped to push bond yields a little lower and knock some wind out of the sails of the inflation bulls.

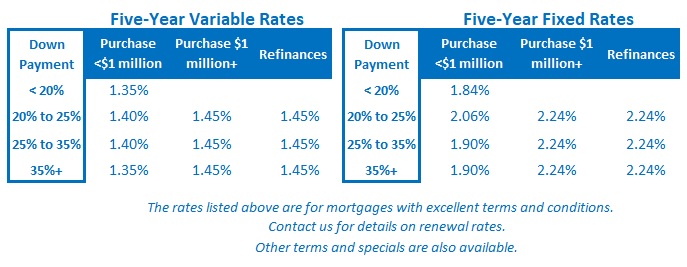

The Bottom Line: Last week’s disappointing employment data helped to push bond yields a little lower and knock some wind out of the sails of the inflation bulls.

Five-year fixed and variable rates were largely unchanged last week and are likely to remain at current levels for at least the short term.