The Fight Between the Bond Market and the Bank of Canada

March 15, 2021A Recap of Recent Posts

March 29, 2021In last week’s post I explained that the bond market and the Bank of Canada (BoC) are currently in a fight about future inflation.

In one corner we have bond-market investors driving up Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields (and the fixed-mortgage rates that are priced on them) over fears of rising inflation. To wit, both the five-year GoC bond yield and average five-year fixed mortgage rates have surged about 0.50% higher over the past few weeks.

In the other corner, the BoC is predicting that the current inflation run-up will prove transitory, and it just doubled down on keeping its policy rate (which our inflation variable mortgage rates are priced on) at 0.25% until sometime in 2023.

Last Wednesday, the US Federal Reserve took its turn pushing back against the mainstream narrative.

Before I highlight what the Fed said, let’s do a quick recap to explain why US monetary policy impacts Canadian mortgage rates:

- GoC bond yields move in near lockstep with their US equivalents. The recent bond yield spike was primarily a US story, and our bonds were simply taken along for the ride.

- That correlation exists because our economy is heavily integrated with, and dependent on, the US economy. About 80% of our exports are sold into US markets, and about 50% of our imports come from the US. That’s why if the US outlook improves, ours should as well, and why if US inflation takes off, it won’t take long for it to work its way north of the border, through trade.

- Our dependence on US export markets also means the BoC can’t raise its policy rate until the Fed moves first because doing so would cause the Loonie to appreciate against the Greenback and make our exports less competitive. (The BoC recently cited the lofty Loonie as a key concern.)

US bond-market investors have been pricing in higher US inflation based on a combination of factors that include massive new levels of federal government stimulus, wide-scale vaccinations (100 million+) and recent improvements in the economic data.

Prior to last week’s meeting, the consensus expected the Fed to allay concerns about rising inflationary pressures by hinting at plans to taper its quantitative easing (QE) programs and also by moving up the expected timing of its next policy-rate hike.

The Fed did neither.

Instead, it responded just as the BoC had the week before. It committed to maintaining, or even increasing, its QE purchases, and renewed its pledge to keep its policy rate near 0% for years to come. In other words, the Fed just doubled down as well.

Here are five key takeaways from the Fed’s policy statement last Wednesday, and from Fed Chair Powell’s follow-up remarks last Thursday:

- The Fed barely batted an eyelid at the US Federal government’s new $1.9 trillion stimulus program. Its only adjustment was to raise its GDP forecast for 2022 from 3.2% to 3.3%, while at the same time lowering its GDP growth forecast for 2023 from 2.4% to 2.2%.

- Far from making any reference to reducing its QE purchases, the Fed’s latest statement confirmed that it will continue buying at least as much each month until “substantial further progress” is made. That newly added phrase opens the door for the Fed to use QE to push back against further yield rises.

- The Fed’s median dot plot, which is a chart that compiles each individual Fed official’s forecast for its policy rate, has the majority holding it at 0% through the end of 2023. As per my point above, if the Fed isn’t raising until after 2023, neither is the BoC.

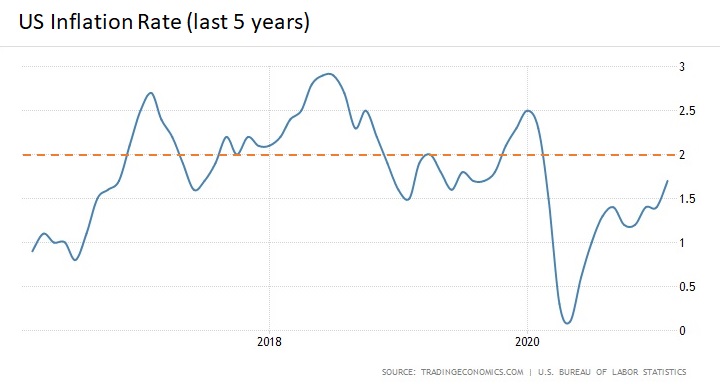

- Fed Chair Powell was adamant that the Fed won’t raise its policy rate until the US unemployment rate falls to 3.5% and inflation averages 2%. The US economy is a long way from those levels. For reference, financial expert John Mauldin notes that the US unemployment rate has only touched 3.5% “twice in the last 60 years”. Given that US inflation has been below 2% for most of the past decade, it will take much more than a short-term spike to bring the average inflation rate anywhere close to 2%. While the Fed hasn’t specified the time scale it will use to calculate average inflation, the rate has stayed well below 2% during the past year. Averaging against that period alone would still require a run above 2% for a material amount of time (see chart).

Central banks usually try to be proactive in anticipating the road ahead, but this time around the Fed is insisting that it will be reactive. If the Fed isn’t going to raise its policy rate until after their unemployment and inflation targets have been reached, we won’t need to guess what it is thinking. (For reference, the US unemployment rate now stands at 6.2% and average US inflation is probably a little above 1% using reasonable assumptions.)

Central banks usually try to be proactive in anticipating the road ahead, but this time around the Fed is insisting that it will be reactive. If the Fed isn’t going to raise its policy rate until after their unemployment and inflation targets have been reached, we won’t need to guess what it is thinking. (For reference, the US unemployment rate now stands at 6.2% and average US inflation is probably a little above 1% using reasonable assumptions.)

Here are my thoughts on why the Fed and the BoC disagree with the bond market:

Policymakers aren’t buying the Roaring 20s narrative – The bond-market consensus thinks we are poised for recovery that will resemble the 1920s, when the end of World War 1 and the Spanish flu ushered in a decade of rapid economic growth and widespread prosperity. In this post I explained why I’m not buying that view, and our central banks clearly aren’t either. They continue to predict that it will take years to repair the economic scarring caused by the pandemic, and they expect permanent behavioural changes to make consumers more frugal and cautious.

The market is focused on next quarter, but central banks are focused on long-term trends: When the pandemic is finally over, our economies will continue to be impacted by long-term deflationary forces which include technological advances, record-high debt levels, and rising dependency ratios. Against that backdrop, central bankers will take all of the inflation they can get.

Not all inflation is the same – The consensus is focused on steadily rising headline inflation, but policymakers have explained that the causes are short-term, technical, and are a result of pandemic-related disruptions. They continue to predict that it will prove transitory, and that’s why they are much less concerned.

Until the pandemic has ended everywhere, it hasn’t really ended anywhere – US vaccination rates are impressive, but the pandemic’s negative economic impacts will continue to limit any country’s chance at a lasting recovery for as long as it ravages other parts of the world.

Central bankers are determined not to repeat past mistakes – One of the key lessons of the Great Depression was that the US Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy at the wrong time, which led directly to economic collapse and then failed to provide enough support during the ensuing crisis, which deepened its impact and extended its duration. Our central bankers’ determination not to repeat the same mistakes this time make them much more willing to err by doing too much, rather than not enough.

Here is one final thought I keep coming back to.

Normally the risk of higher-than-expected inflation would be keeping central bankers up at night.

The BoC and the Fed know that recommitting to their extraordinary monetary policies is likely to exacerbate inflation fears, and if enough people respond based on that belief, it could easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The fact that the BoC and the Fed just stared down financial markets without blinking means they’re willing to risk higher-than-expected inflation in order to avoid what’s behind door number two. That thought should give pause to even the most ardent inflationists. The Bottom Line: Lenders continued to raise their fixed rates last week, while variable rates held steady. For the reasons above, as well as the ones I outlined in this recent post, I continue to believe that for most borrowers, variable rates are a better option than today’s fixed-rate alternatives.

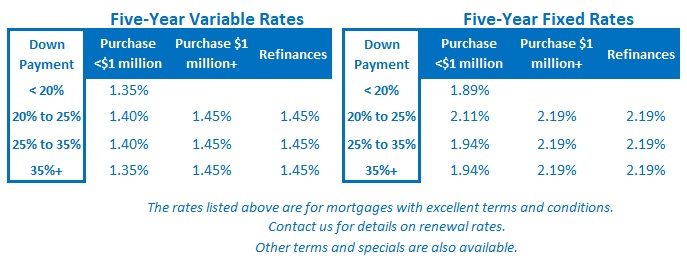

The Bottom Line: Lenders continued to raise their fixed rates last week, while variable rates held steady. For the reasons above, as well as the ones I outlined in this recent post, I continue to believe that for most borrowers, variable rates are a better option than today’s fixed-rate alternatives.