Fixed Mortgage Rates Rise on Inflation Fears – But Are These Concerns Warranted?

March 1, 2021The Fight Between the Bond Market and the Bank of Canada

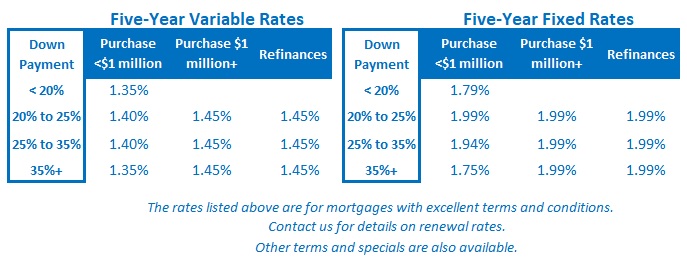

March 15, 2021Five-year fixed mortgage rates have reversed course and risen by about 0.25% recently, while five-year variable mortgage rates have continued to inch lower.

The rather sudden widening of the gap between these two options makes now a good time to revisit the age-old fixed vs. variable question.

Let’s start with a quick look back at how we reached this point.

When COVID hit last March, the Bank of Canada (BoC) responded with three 0.50% emergency policy-rate cuts in rapid succession. By the end of that month, it had slashed its policy rate to 0.25%. At the same time, the five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield that our five-year fixed mortgage rates are priced on also plunged, falling from 0.86% in mid-March down to 0.42% by mid-April.

Somewhat surprisingly against that backdrop, fixed mortgage rates actually moved higher. Five-year fixed mortgage rates that had hovered in the high 2% range in early March spiked into the mid 3% range.

While GoC bond yields had fallen, lenders added new COVID-related risk premiums to mortgage rates as a defensive response to the uncertainly that lay ahead. We were in the midst of the first wave of lockdowns and had just seen record-setting job losses. Lender phone lines were jammed with calls from borrowers wanting to defer their mortgage payments (and toilet paper was in short supply – for good reason).

Variable mortgage rates, which had been hovering in the high 2% range, fell, but only by about 0.75%, or around half the 1.50% in cuts made to the BoC’s policy rate. Lender prime rates, which are used to set variable mortgage rates, fell alongside the BoC’s policy rate, but the variable-rate discounts off prime, which had been as a high as 1.00% before the pandemic, all but disappeared.

(That meant that existing variable-rate borrowers saw their rates drop by the full 1.50%, because lender prime rates dropped in lockstep with the BoC’s policy rate, but by removing their discounts off prime on new business, the rates offered to new variable-rate borrowers were only 0.75% lower.)

I published this fixed vs. variable post at the time. In it, I predicted that the risk premiums driving our mortgage rates higher would prove temporary, and I advised that borrowers who needed to close on a mortgage while this anomaly was occurring would be better served with a variable-rate mortgage.

I highlighted these advantages, all of which still apply today:

- Variable rates were lower than fixed rates, so variable-rate borrowers started out saving right off the bat.

- Variable rates can be converted to fixed rates at any time and at no cost. Last spring, I predicted that lender COVID-related risk premiums would recede, and that variable-rate borrowers would then have the option to convert to much lower fixed rates. (Both predictions came true.)

- Variable-rate mortgage contracts can be broken by paying a penalty of only three-months’ interest. That means if you want to convert and your lender doesn’t offer you a competitive conversion rate, you can break your mortgage and source the best rates available in the market at minimal cost.

- Variable-rates were (and are) almost guaranteed not to rise for years to come. In addition to slashing its policy rate last March, the BoC pledged to keep its policy rate low for “a long time”. Then, in its policy statement last July, the BoC was even more explicit and committed to not raising its policy rate until sometime in 2023. While there is always a risk that variable rates might rise, the BoC’s forward guidance greatly reduces that likelihood over at least the next two years.

- More recently, the BoC has speculated about cutting its policy rate again. While the Bank has made it clear that taking its 0.25% policy rate negative is not an option, it has floated the idea of making a micro-cut to its policy rate if circumstances warrant. (It would most likely do this in response to the Loonie’s continued rise against the Greenback and/or to our weakening employment backdrop, which I explain in detail here.)

So, if variable rate mortgages are cheaper, more flexible, and currently come with a near guarantee from the BoC that they will not rise for at least two years, why are most borrowers still opting for fixed rates?

Most people are generally risk averse when they make major financial decisions, and the risk that variable rates might rise never completely goes away. The pandemic has increased volatility and heightened uncertainty, and it makes sense that people are being cautious in response.

Today, the mainstream news media are rife with warnings about rising inflationary pressures to come. Bond yields have spiked higher in response, and they have taken fixed mortgage rates along for the ride. While variable rates are still nailed to the floor, I am now fielding a lot of calls from variable-rate borrowers wondering if they should convert to a fixed rate before the cost of their conversion parachute rises even higher.

It is also easier for mortgage professionals to recommend fixed rates. If they end up costing more, the extra cost can be justified as paying for rate insurance that the borrower didn’t end up needing. Conversely, if variable rates prove more expensive, which is always a risk, anyone advocating that option can be left to feel that they have unduly risked someone else’s money. (Although either way, making the wrong recommendation will cost the borrower more.)

Fixed rates are clearly the more popular choice these days, but are today’s variable mortgage rates really that risky?

Consider the following:

- Anyone applying for a mortgage today must qualify using the stress-test rate of 4.79%, and that greatly reduces the risk that variable-rate increases will ever make your mortgage truly unaffordable. The stress-test ensures that even though you will be starting out with a variable rate in the 1.50% range, you actually can afford for the rate to rise all the way to 4.79%, even though that seems highly unlikely. I haven’t heard anyone who isn’t wearing a tin-foil hat try to argue that variable rates are going to more than triple over the next five years.

- Five-year variable rates have outperformed five-year fixed rates about 85% of the time over the past twenty-five years. While rates have generally fallen during that stretch, which gives a natural edge to variable rates, there were also periods where five-year variable rates rose above their fixed-rate equivalents for periods of time. Despite that, variable rates still cost less over the full five years. Simply put, variable rates have an inherent cost advantage over fixed rates that tilts the odds in their favour most of the time.

- Even if the BoC is forced to raise its policy rate to bring inflation back to its 2% target, today’s elevated government- and household-debt levels mean the Bank won’t have to raise it by as much as would have been required in past cycles to bring inflation to heal. The BoC has repeatedly acknowledged this reality, and that makes one or two gradual increases of 0.25% far more likely than a spike of 1%+ that many borrowers instinctively fear.

- The BoC isn’t likely to move its policy rate higher until the US Federal Reserve moves first – to avoid having the Loonie appreciate further against the Greenback. The Fed recently adopted a new approach called average inflation targeting (AIT), which means that it wants inflation to average 2% over the long run. To do that, the Fed will allow extended periods of below-target inflation, like the US economy is experiencing now, to be followed by periods of above-target inflation. That has pushed out the expected timing of the Fed’s next rate hike to 2024, and for all intents and purposes, that pushes out the BoC’s rate-hike timetable as well.

- The inflation narrative is overblown. I just don’t buy the consensus narrative, and I detail my reasons why in this recent post.

Finally, it should be said that five-year fixed rates come with risk as well.

As previously mentioned, bond-market investors have pushed bond yields sharply higher of late, and that has caused fixed mortgage rates to spike as well. Anyone opting for a five-year fixed-rate mortgage today may end up locking in a temporary rate rise for the next five years.

If I’m right about inflation fears being overblown, and if rates fall back once the current run-up tails off, today’s fixed rates will end up being much more expensive than their variable-rate equivalents (and that will be especially true for anyone whose fixed-rate mortgage contract comes with massive interest-rate differential penalties, which I warn about here).

Of course, cost is not the only factor you need to take into account when making the fixed/variable decision. If you’re going to lose sleep at night worrying that your rate will rise, locking into a fixed rate might be worth it because you can’t put a price on peace of mind. But if you can tolerate some uncertainty and still sleep well, for the reasons outlined above, I think variable rates will end up being the cheaper option over the next five years. The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to move higher last week whereas five-year variable rates moved a little lower. As the gap between five-year fixed and variable rates widens, so too should the appeal of variable rates – at least through the eyes of this mortgage blogger.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to move higher last week whereas five-year variable rates moved a little lower. As the gap between five-year fixed and variable rates widens, so too should the appeal of variable rates – at least through the eyes of this mortgage blogger.