Don’t Appreciate the Mortgage Stress Test Yet? Give It Time

August 24, 2020Employment Data Confirm Our Recovery Is Still in the Early Innings

September 8, 2020If you want to know where mortgage rates are headed, inflation holds the key.

If inflationary pressures remain low, the Bank of Canada (BoC) will keep its policy rate at its current 0.25% level for the foreseeable future and our variable mortgage rates, which are priced on the BoC’s policy rate, will remain at today’s rock-bottom levels for years to come. Against that same backdrop, our Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields, which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on, will either hold steady or continue falling.

If inflationary pressures build, GoC bond yields will increase, and the longer the bond, the more its yield will rise in response to changes in the outlook. Rising bond yields would increase lender funding costs which would, in turn, push fixed mortgage rates higher. Under this scenario, the BoC would likely be more patient than the bond market and allow inflation to run a little hot while determining whether the uptick would be sustained. But at some point, the Bank would start raising its policy rate to keep inflation on or around its 2% target, and variable mortgage rates would increase in lockstep.

So, if our mortgage rates follow the path of inflation, how do we figure out where it is headed?

Easier said than done.

Just measuring inflation is tough to do.

Statistics Canada uses a wide sampling of weighted prices to construct the Consumer Price Index (CPI) as a measure of overall inflation over the most recent twelve months. But this broad measure can be quite volatile when prices with large CPI weightings fluctuate. For example, food and energy prices move around a lot and can have a big effect on the CPI index. To address this issue, Stats Can also publishes subindexes, which exclude the most volatile inputs and measure what it calls core inflation (which you can read more about here).

The pandemic has made it even harder to accurately measure inflation because the price weightings used in the indices are based on historical activity and aren’t adapted to our post-COVID spending habits. For example, cheaper airline flights are now helping to offset rising food prices in the overall CPI, but that isn’t giving us an accurate measure of real inflationary pressures because almost no one is flying and everyone still needs to eat.

To address this issue, Stats Can recently released a new inflation gauge called its Analytical price index. This measure increases the price weightings on items that Canadians are buying more of in response to COVID and decreases the weightings on items that are experiencing lower sales. (Thus far it shows inflationary pressure falling, but by less than the more traditional overall CPI.)

Measurements aside, the public’s perception of where inflation is headed is just as important as what the current data say. If consumers believe that prices will be higher tomorrow, they will buy more today, and the consequent increase in demand will push prices higher – whether they were originally headed that way or not. On the other hand, if consumers believe that prices will be lower tomorrow, they will forgo all but the most essential purchases today, and that reduced demand will cause prices to fall.

So, the next key question is, “Where do people think inflation is headed?”

Unfortunately, there is no simple answer to this question.

Some people are convinced that inflation is set to rise while others are just as certain that it will remain low for years to come. Here are five points supporting each view.

Inflationary pressures will rise because …

- Governments are racking up huge deficits, and central banks are printing money to pay for them. When there is a massive increase in the supply of money available and little or no change in the quantity of goods available, inflation should take hold.

- Unlike during the financial crisis of 2008 when newly printed money sat on bank balance sheets and didn’t circulate, this time government stimulus programs are putting money straight into the hands of consumers (a policy action referred to as “helicopter money”). When all of this extra money is spent, it should fuel a rise in prices.

- Average incomes have actually increased since the start of the pandemic. In the U.S., seven out of every ten people who lost their jobs have received more in government payouts than they had earned over an equivalent period in their previous job – and those numbers are similar in Canada. Rising incomes should also normally stoke inflation.

- Globalization reduced the price of just about everything, but we are now entering a period of deglobalization where production costs rise as supply chains are repatriated. Deglobalization has also been accompanied by a rise in tariffs, and this too has pushed prices higher.

- Changes required in response to COVID have raised business operating costs in myriad ways.

Inflationary pressures won’t rise because …

- Ultra-low rates and profligate government spending are nothing new. Most countries have been on this path in one form or another for the past decade, and inflation hasn’t taken hold, even when accompanied by a relatively tight labour market. The traditional economics textbooks have been wrong for a long time now.

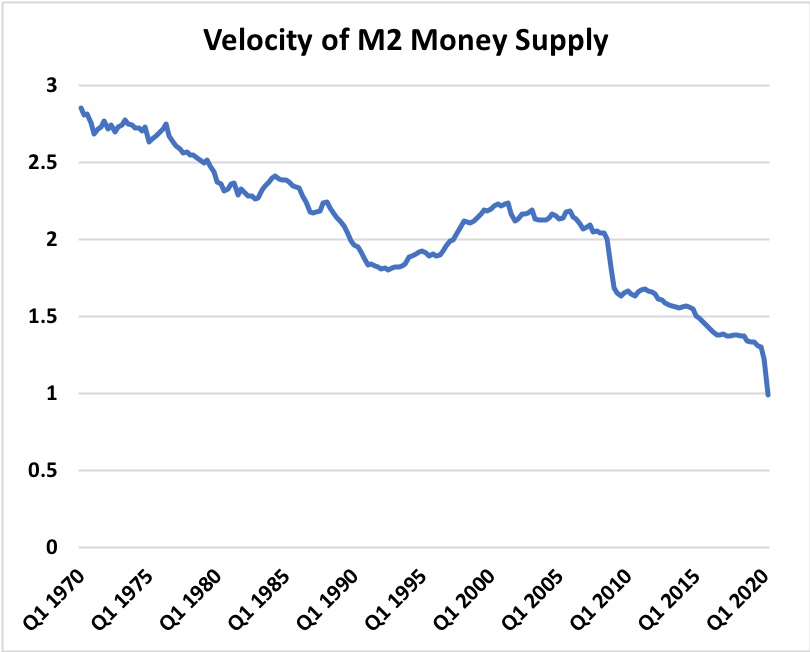

- Governments are putting money directly into the hands of consumers but, so far, a lot of that money is being saved rather than spent. To wit, our household saving rate, which had averaged about 3% for years, spiked all the way up to 28% in the second quarter of 2020. Not surprisingly, the rate at which money is circulating through our economy just hit a record low. Check out the chart below courtesy of analyst Ben Rabidoux of North Cover Advisors. (It doesn’t portend rising inflationary pressures on the horizon.)

- While some prices are rising, the impact on overall inflation is muted because consumers are choosing to trade down rather than pay higher prices. (Discount retailers, like Dollar Stores, are currently reporting record results.) Consumers are also forgoing big purchases, in part because of increased caution but also because of lifestyle changes that may end up being permanent (such as choosing to ride a bike instead of buying a second car).

- Inflationary pressures typically rise when our economy’s output gap closes. (Reminder: The output gap is the gap between our economy’s actual output and its maximum potential output.) The BoC estimates that our output gap is now as wide as it has been in the past decade, and that leaves a substantial amount of slack for our economy to absorb when it kicks into higher gear at the end of our current deep recession.

- Today’s elevated debt levels across the board (governments, businesses and consumers) are diverting funds toward interest payments and away from spending that would otherwise increase demand and eventually lead to higher inflation. (Although fortunately, this effect is muted by our extremely low interest rates.)

The fact is that we will have both too much and too little inflation in the future. It is cyclical after all, so it all comes down to timing.

For my part, I don’t expect significant inflationary pressures to take hold for some time yet. If the rate at which our money circulates through our economy does finally increase, then hold on to your hat. But the chart above goes back fifty years and the current trend has been a long time in the making.

On a related note, if inflation does start to run hot, I think our policy makers will be more tolerant of it than they have been in the past.

For one thing, inflation erodes the cost of debt repayment. Governments will likely prefer a little inflation to help with their debt repayments and reduce the political pain of having to raise taxes to do so. Central bankers also prefer to err on the side of too much inflation because their monetary-policy tools are better suited to reining it in than increasing it.

On that note, last week the U.S. Federal Reserve announced a major policy shift. Instead of targeting a fixed inflation rate of 2%, going forward the Fed will instead aim for an average of 2% inflation.

This means that Americans can now expect periods of below-target inflation, like the one the U.S. economy is in now, to be followed by periods of above-target inflation up to the point where inflation reaches a 2% average. This approach means that the longer a period of below-target inflation goes, the more room (and expectation) the Fed is creating for above-target inflation in future.

That shift provides a pretty clear indication of the Fed’s current inflation outlook.

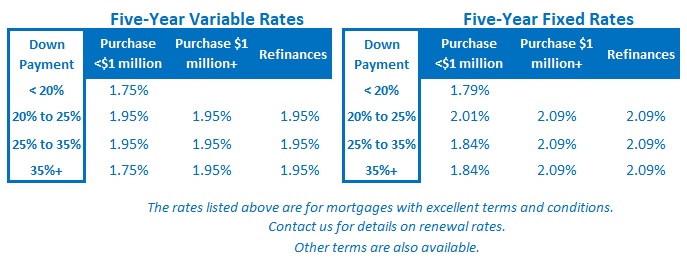

The Bottom Line: Fixed-mortgage rates dropped a little last week while variable mortgage rates held steady. I expect the current trend of gradually decreasing mortgage rates to continue over the short term.