A Theory on Why CMHC President Evan Siddall Went Rogue Last Week

August 17, 2020Are We Headed for Too Much Inflation or Not Enough?

August 31, 2020Our policy makers have a love-hate relationship with our residential real-estate sector.

On the one hand, the sector has provided our economy with a consistent boost over a period when business investment and export growth have disappointed. But on the other hand, too much residential real-estate investment can be detrimental because the elevated debt levels associated with it can sap growth over time.

Balancing real estate’s risk/reward trade-off has been a tricky proposition for our regulators.

When the Great Recession hit and U.S. house prices crashed in 2008, our policy makers began to modify our mortgage-underwriting rules to guard against the risk that what happened there could happen here. Since then, they have implemented seven rounds of mortgage rule changes, the most significant of which was the introduction of the mortgage stress-test rate in late 2017.

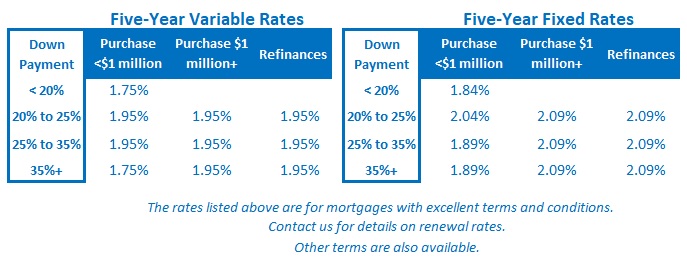

To quickly review, the mortgage stress test requires that residential mortgage applications be underwritten using a rate that is much higher than actual market rates. For example, five-year fixed and variable mortgage rates are offered in the 2% range today, but mortgage applications are qualified using the current stress-test rate of 4.79%. That hefty premium reduces everyone’s maximum borrowing capacity by about 20%.

While the stress test hasn’t won any popularity contests, it has proven to be a prudent measure that has helped our economy in several ways:

- It reined in real-estate speculation in hot regional markets.

- It ensured that mortgage borrowers can afford significant rate rises from today’s record-low levels.

- It reduced the stimulative impact of the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) COVID-related policy-rate cuts and plunging Government of Canada bond yields.

Let me expand on that last point.

When COVID hit, the BoC lowered interest rates across the board as part of its effort to counter the negative impacts from what it referred to as “the steepest and deepest economic decline since the Great Depression.” Although rates fell and actual borrowing costs plummeted, the stress-test rate barely budged. That left everyone’s borrowing capacity essentially unchanged. Despite this, real-estate activity in regional markets quickly rebounded, and house prices resumed their upward climb.

If you think your local real-estate market is hot right now, imagine what it would look like without the stress test keeping a lid on everyone’s borrowing capacity.

The stress test may prove useful in different ways going forward.

Consider the following:

- If our real-estate markets falter, the BoC has the option to respond by reducing or eliminating the stress test, and that may be preferable to other unconventional monetary-policy options, such as a negative policy rate.

- The stress-test rate has essentially held steady as real rates have dropped, and it can do the same if real rates go the other way. Increased borrowing costs would still be a headwind, but if borrowing capacities were largely unaffected, that would help to lessen the blow.

While the stress test is often maligned, as strange as it may seem at the current time, its ability to stimulate growth and/or cushion the impact of higher rates may swing popular opinion in its favour in the years ahead.

To be clear, I am not advocating for any reduction in the stress-test rate at this time. The current momentum in our regional real-estate markets doesn’t call for that. But in future, if that momentum slows, the stress-test buffer that was built up when our real-estate markets were strong can be reduced to provide a powerful stimulus if they weaken.

(Side note: The stress test isn’t perfect. It needs tweaking. For example, the BoC currently sets this key benchmark using the Big Six banks’ purely symbolic five-year posted rates, which as I explain in this post, makes no sense. In fairness, our federal Ministry of Finance was set to modify the stress test in April, but those plans are now, understandably, on hold.)

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates fell a little once again last week, and variable rates held steady.

The BoC has been unusually clear about its policy rate 0.25% not rising for “a long time”. It has also said that it won’t go any lower, so anyone who has an existing variable mortgage rate isn’t likely to see it move in either direction for quite a while.

That said, lenders have been increasing the variable-rate discounting they offer to new borrowers as their COVID-related funding-risk premiums continue to melt away. Five-year fixed mortgage rates have also fallen steadily of late for the same reason.

I expect both of these trends to continue.