The Must-Have Mortgage Toolkit for Every Home Buyer

July 6, 2020The Bank of Canada’s Surprising Admission That Ultra-Low Mortgage Rates Are Here to Stay

July 20, 2020Our economy added 290,000 new jobs in May, which was a record monthly gain.

That record didn’t last long.

Last week, Statistics Canada confirmed that we more than tripled that total in June by adding another 953,000 jobs.

In normal times, that number of job gains would send bond yields soaring as the bond market priced in rising inflationary pressures and imminent Bank of Canada (BoC) policy-rate rises.

I’m sure you don’t need to be reminded that these are not normal times.

Here are a few data points to drive that message home:

- Before the current COVID crisis, our previous record for monthly job losses was 124,800 (in January 2009), and our record for job losses over an extended period was 612,000 (which occurred over 17 months during the 1981-1982 recession).

- In March and April of this year, we lost a total of 3 million jobs, and an additional 2.5 million Canadians worked less than half of their normal hours.

- While the record job gains over the last two months are encouraging, when the total gain of approximately 1.25 million jobs in May and June is netted out against the 3.5 million jobs lost over March and April, we’re still down more than 2.25 million jobs since the COVID crisis began.

Bluntly put, we’re going to get tired of reading about massive monthly job gains long before they will have any material impact on our mortgage rates.

The BoC and the bond market focus primarily on inflation, and employment gains won’t put upward pressure on inflation until our output gap is near to closing. (Reminder: Our output gap measures the gap between our economy’s actual output and its maximum potential output.)

Our economy needs to recover all of the jobs it lost in March and April and add more on top before our output gap will close. And not all of the lost jobs are coming back. Our economy won’t recover until entirely new jobs are created in their place. This will take years.

Employment momentum also drives consumer spending, which accounts for more than half of our total GDP. Not surprisingly, that spending plummeted in the first quarter of 2020. Not to be all doom and gloom, but the worst may be yet to come.

Our federal government has provided unprecedented levels of support to Canadians during this crisis through the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) program. So much so that average Canadian incomes have actually risen since the crisis began – and in some cases, workers who return to lower-paying jobs will actually see their incomes decline.

CERB has temporarily, and at great cost, cushioned the negative economic impacts of our massive job losses, but the program is currently capped at 24 weeks. Anyone who lost their job in February will be covered until sometime in August. When unemployed workers cap out, our consumer spending data will start to reflect the full impact of all that lost employment income for the first time.

Consumer spending has also been impacted by a spike in our household saving rate, which nearly doubled from 3.6% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 6.1% in the first quarter of 2020. Canadians are quite reasonably choosing to bolster their financial reserves in the face of so much economic uncertainty. Although this is a responsible reaction for individuals, on a macro-economic level, more saving and less spending will further slow our rate of recovery.

The long-term damage done to our employment market and the related impacts on consumer spending are underpinning a widespread consensus that interest rates (and mortgage rates) won’t be headed higher for quite some time to come. Even the BoC recently speculated that rate rises aren’t likely until at least 2022 or 2023.

Against that backdrop, even record setting monthly employment gains won’t impact our mortgage rates.

The Bottom Line: The BoC meets this week and will release its first Monetary Policy Report under its new Governor, Tiff Macklem. I expect caution and uncertainty to be the main themes, in part because it is clear that it will take years for our employment markets to recover, and relatedly, because of the headwinds that our drawn-out recovery will exert on our incomes, consumer spending, and inflation.

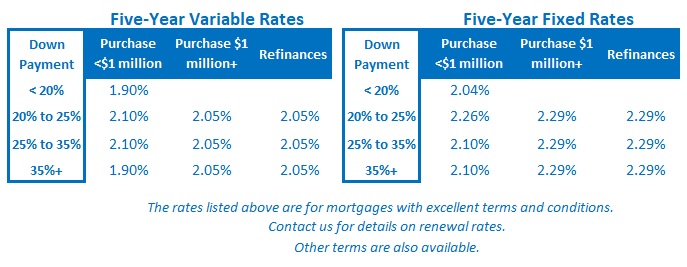

Five-year fixed and variable rates held steady last week, but all of the recent momentum suggests that they are likely to continue their gradual decline over the near term.