The Bank of Canada Cuts Again and Policy Makers Get Creative

March 30, 2020Our New Canadian Mortgage Landscape?

April 13, 2020If you need a mortgage now and you don’t already have a commitment in place, a variable rate seems like the clear choice – either for a purchase, refinance or renewal.

Normally I would hedge a little because every borrower’s circumstances are different, and I realize that some people just aren’t wired for variable-rate risk, but normal isn’t a word we’re using much these days.

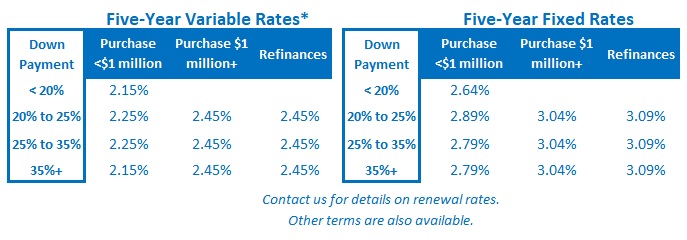

To explain why I write that, let’s start with a snapshot of where rates are at the moment:

- Five-year fixed rates are now offered in a range between 2.64% and 3.09%. (Where you fall within that range depends on your loan-to-value ratio and whether your mortgage is eligible for default insurance.)

- Five-year variable rates are now widely available at anywhere from prime minus 0.30% to prime plus 0.05%, which works out to between 2.15% and 2.50%.

Both fixed and variable rates have moved higher of late.

My post from last week explains how we got here, but suffice to say, lenders have added significant risk premiums to their lending spreads. Gross spreads that are normally between 1.25% and 1.50% have been blown out to 2.00% to 2.50%, and that doesn’t seem likely to change until we are past the economic shocks of COVID-19 and the oil-price war.

The recent rate run-up has had incrementally less impact on variable rates because the Bank of Canada (BoC) just slashed its policy rate from 1.75% to 0.25%.

Variable rates had been higher than fixed rates for quite a while but they are now suddenly 0.50% cheaper, and our current economic backdrop makes it highly unlikely that they will rise in the foreseeable future. (At some point all of the debt we are adding to the financial system in response to the current crisis should lead to higher interest rates, but that day seems a long way off.)

So, what is that 0.50% difference in rate worth?

A $300,000 five-year fixed-rate mortgage with a rate of 3.04% amortized over 25 years will cost you $8,950 over the next twelve months. The same mortgage borrowed at a five-year variable rate of 2.45% will cost you $7,215, for a total saving of $1,735 in just the first year.

That will buy you a lot of toilet paper, even at today’s prices.

Variable-rate mortgages also have a unique feature: convertibility.

If variable rates defy long odds and end up moving higher, you can convert to a fixed-rate term that is equal to or greater than the time remaining on your current mortgage at no cost. (There is no such option to convert from a fixed rate to a variable rate.)

Variable-rate mortgages also aren’t as expensive to break, and that increases your flexibility.

The penalty to break a variable-rate mortgage is only three months’ interest so you can avoid the dreaded interest-rate differential penalty that haunts fixed-rate mortgage borrowers. A reasonable penalty increases your potential saving if you want to break early to take advantage when fixed rates drop or variable-rate discounts widen, and it will minimize cost if you want to refinance or sell.

Now for a word about home equity lines of credit (HELOCs).

I watched a recent clip of Doug Hoyes interviewing Ben Rabidoux about HELOCs, and while he apparently took heat for his view that lenders will likely start cutting them back, I second it.

HELOCs are great tools while they last but they could easily become an endangered species.

For starters, HELOCs can’t be insured against default so lenders have to back them with their balance sheets. That means they own the risk – and that’s probably why HELOCs are demand loans, which allow the lender to call them or change the terms associated with them, at any time. (They can’t do that with mortgage contracts.)

The job losses we are now seeing are staggering. Stretched borrowers may find their unused HELOC capacity eliminated and/or their outstanding balance converted to an amortizing loan.

Here is an example of how that change would impact monthly cash flow:

- A $300,000 HELOC balance at a rate of 2.95% has an interest-only payment of $737.50/month.

- If that balance is converted to a $300,000 mortgage at the same rate of 2.95% amortized over 30 years, the minimum required payment would increase to $1,252.

- Going from an interest-only HELOC payment to an amortizing mortgage payment would cost this stretched borrower an extra $515/month in cash flow.

The extent to which this happens will depend largely on real estate prices. If they fall materially, capping unused HELOC capacity will be an easy way for lenders to limit further downside risk with the stroke of a pen.

If you don’t see this as a real possibility, I ask you to click on this chart from Len Kiefer below (hat tip to Ben Rabidoux).

It shows a history of initial U.S. jobless claims from January 1967 until now (the Canadian chart would look essentially the same). The U.S. economy saw seven recessions of varying lengths over that fifty-three-year period.

This time is different.

The Bottom Line: Fixed and variable mortgage rates have both risen because lenders have (understandably) added significant risk premiums to their lending spreads. Against this new backdrop, the variable rate emerges as the clear choice because it saves you money now while also maximizing ongoing flexibility.

The Bottom Line: Fixed and variable mortgage rates have both risen because lenders have (understandably) added significant risk premiums to their lending spreads. Against this new backdrop, the variable rate emerges as the clear choice because it saves you money now while also maximizing ongoing flexibility.

On a different note, mortgages aren’t going anywhere but HELOCs may be, so don’t take your unused HELOC limit for granted.

4 Comments

I enjoyed your post a lot David. You explain things very clearly and easily for readers to understand. Thanks a lot

Thank you for your note Jane. Nice of you to say.

Dave

Great info you provide. Thx.

What are the chances the discount on variable rates will continue to widen to previous levels? They sure compressed quickly as the BOC cut rates.

Hi Mike,

Very tough to predict. So much unknown at the moment.

Glad you enjoyed the post.

Best,

Dave