Mortgage Basics: Term vs. Amortization

February 20, 2020How Much Longer Will the Bank of Canada Stand Pat?

March 2, 2020Last week our federal government announced that on April 6, 2020 it will change the way the Bank of Canada (BoC) calculates the stress-test rate that lenders use to qualify all insured mortgage applications.

In today’s post I will explain what changed and offer five key observations relating to it.

First, a quick refresher:

- The term “insured mortgage” refers to any mortgage where either the borrower or the lender pays for mortgage-default insurance.

- Borrowers who are purchasing a property with a down payment of less than 20% must purchase mortgage-default insurance. When the down payment is 20% or more, the borrower and/or the lender has the option of purchasing default insurance (to lower the interest rate).

- Today if a borrower applies for an insured mortgage that comes with a rate of 2.69%, they must qualify using the current stress-test rate of 5.19%.

- Last week’s announcement applies to only insured mortgages. Thus far, there has been no formal announcement about changes to the stress-test rate used for uninsured mortgages, although that is expected soon (more on that below).

Here is a comparison of how the stress-test rate for insured mortgages is calculated now and how it will be calculated as of April 6:

- Today the insured stress-test rate is calculated using the mode of the Big Six Bank’s current five-year posted rates (which I explain in more detail in this recent post). The current methodology is flawed because the Big Six don’t actually lend at their posted rates, and they don’t adjust them dynamically in response to market changes. (To cite a recent example, average five-year fixed rates have fallen by nearly 1% over the past twelve months, and the stress-test rate has only decreased from 5.34% to 5.19% over that same period.)

- Effective April 6, the stress-test rate for insured mortgages will be set each week by adding 2% to the average interest rate on insured mortgage applications over some prior period (with more details on that look-back period to follow).

- The federal government estimates that this change in methodology will lower the current stress-test rate from 5.19% to about 4.89%.

Here are five key observations relating to this change and how it will likely impact borrowers:

- This change will likely hurt affordability in our hottest real-estate markets over the short term.

At first this statement may seem counterintuitive. If the stress-test rate drops from 5.19% to 4.89%, shouldn’t that improve affordability? In theory, yes. But if there are five bidders for a property and they can all suddenly increase their maximum mortgage amount, the price of the property is likely to be pushed higher, and that will make it less affordable to whoever makes the winning bid.

Furthermore, while the stress-test rate drop will only increase borrowing capacity by about 3% to 4%, the psychological impact of the stress-test rate drop could prove much more significant. If buyers believe that the lowered stress-test rate will fuel more demand, that could exacerbate their fear of missing out and make them more desperate to seal a deal, thereby driving prices higher and further reducing affordability.

- The stress-test rate will be more dynamic, but also more volatile.

The stress-test calculation tweak is a welcome change because it ties this benchmark directly to real market rates. But that will also make it more volatile. Stretched borrowers, who are pushing to buy at the top of their affordable price range, run the risk that a property they can afford one week becomes unaffordable the following week if the stress-test rate edges up.

The BoC can smooth out some of this volatility by incorporating a longer time horizon when calculating the average insured mortgage rate, and lenders may also be allowed to grandfather pre-approvals back to the stress-test rate that was in effect at the time they were issued, but these specific details have yet to be clarified.

- The new stress-test rate will increase transparency.

The stress-test rate will be calculated by taking the average interest rate of the mortgage applications received by all three of our default insurers (CMHC, Genworth and Canada Guaranty). Borrowers will be able to compare the rate they are being offered against the average to see if they are getting a good deal (and if it might be worth it to shop around).

Surprisingly, about two-thirds of Canadian mortgage borrowers still walk into the bank that handles their daily banking, and many accept whatever they are offered without seeking alternatives (which can be an expensive mistake, as this post explains).

- The stress-test rate for uninsured mortgages will also soon be changed, but calculating the average uninsured rate will be more challenging.

Last week the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) announced that it was considering similar changes to the stress-test rate for uninsured mortgages. (Spoiler alert: It’s going to happen.) While I expect that OSFI will also settle on some sort of average rate + 2%, choosing the right methodology will be more difficult.

When the BoC wants to figure out the average insured mortgage rate, it can simply combine the aggregated data from our big-three mortgage-default insurers. But on the uninsured side, aggregating the data will be more complicated. Will the BoC compile data from individual lenders? If so, how many? The Big Six don’t like to share their data, but if they are compelled to do so, this might be one time when they will be happy to have their average mortgage-rate details submerged in with a larger, market-wide pool of lenders.

Regardless, uninsured borrowers would also benefit from the increased transparency of a market-based benchmark.

- The debate about how much stress the stress test should test will now intensify.

Now that our regulators have set a clearly identified benchmark of a 2% premium over current market rates, expect more ink to be spilled arguing about whether that level is appropriate for mitigating the risk of higher rates at renewal.

On that note, here’s something most people don’t know.

The average borrower who is stress tested at a rate of 4.89% today will actually be able to afford a higher rate than that at renewal, all else being equal.

That’s because today the vast majority of Canadian borrowers opt for a five-year rate, and that means their mortgage principal will be reduced by five years’ worth of payments by the time they are up for renewal.

Here is an example of how that impacts a borrower’s tolerance for higher rates at renewal:

- Assume a borrower qualifies for a $480,000 five-year fixed-rate mortgage at 2.69% using a stress-rest rate of 4.89%. The stress-test payment used to qualify that borrower is $2,762.

- At renewal, the borrower’s balance will be down to $407,805. If rates have risen to 4.89% by then, the borrower’s payment won’t be the $2,762 the stress-test rate was originally based on, it will be $2,656 (because their balance will be lower after five years). For that borrower’s payment to be equal to $2,762 at renewal, their rate would have to rise to 5.37% (or a little more than double their current rate).

Is stress-testing every borrower for a doubling of their interest rate over the next five years appropriate?

Get your popcorn ready.

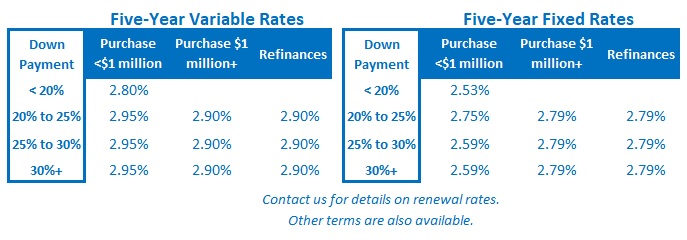

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed and variable rates held steady last week and, barring any coronavirus curve balls, are likely to do so again this week.

The big news was the federal government’s announcement that the stress-test rate for insured mortgages will soon be based on real market rates, instead of the Big Six’s posted rates.

Interestingly, while this long overdue change will likely reduce today’s stress-test rate from 5.19% to 4.89%, for the reasons outlined above, it will also likely decrease affordability over the short term and make the stress-test rate more volatile going forward.

Nonetheless, this was a much-needed change, and OSFI has indicated that a similar tweak to the stress test used for uninsured rates isn’t far behind.