Forecast for Canadian Fixed and Variable Mortgage Rates in 2020

January 13, 2020Canadian Mortgage Rates Move Lower After Bond Yields Drop on Coronavirus Fears

February 3, 2020 The Bank of Canada (BoC) left its policy rate unchanged last week, as widely expected, and that means variable mortgage rates will remain at their current levels for the time being.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) left its policy rate unchanged last week, as widely expected, and that means variable mortgage rates will remain at their current levels for the time being.

The Bank also issued its latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR), which provides us with its quarterly assessment of economic conditions both at home and abroad.

The January MPR, along with the BoC’s accompanying commentary, conceded more uncertainty about the current conditions. This dovish shift led to a drop in Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields, which our fixed-rate mortgages are priced on, and lenders started lowering their five-year fixed mortgage rates shortly thereafter.

Today’s post will provide highlights from the BoC’s latest communications along with my take on how its more cautious outlook will likely impact both our fixed and variable mortgage rates going forward.

First a recap of current conditions.

The bond market and the BoC haven’t seen eye to eye for some time now.

Over the past year, the Bank has offered a relatively optimistic assessment of our economy’s prospects, while the bond market has reflected a decidedly more pessimistic outlook through its pricing of GoC bonds. (The historical record shows that bond markets are much better economic forecasters than central banks.)

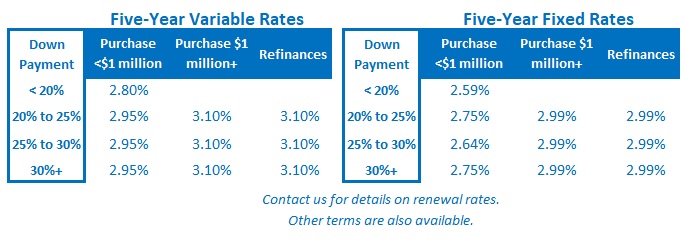

These disparate views caused our bond-yield curve to invert, which happens when short-term bond yields rise above longer term yields. (The inverted yield curve is also the reason that our five-year variable mortgage rates have been higher than our five-year fixed mortgage rates for about a year now.)

The BoC’s latest communications didn’t offer a complete mea culpa to the bond market, but the Bank did acknowledge that our economic momentum hasn’t proven to be as robust as it had previously forecast. To wit:

- “The global economy is showing signs of stabilization” but “there remains a high degree of uncertainty and geopolitical tensions have re-emerged.”

- “The Canadian economy has been resilient but [recent] indicators … have been mixed.”

- Our recent economic data “indicate that growth in the near term will be weaker, and the output gap wider, than the Bank projected in October.”

- “Exports fell in late 2019, and business investment appears to have weakened after a strong third quarter.”

- “Job creation has slowed, and indicators of consumer confidence and spending have been unexpectedly soft.”

- The BoC conceded that the weaker-than-expected data could be a signal “that global economic conditions have been affecting Canada’s economy to a greater extent than was predicted.”

- The only sector of the economy the BoC didn’t sound worried about was residential investment, which the Bank called “robust” for most of 2019 and assessed was “moderating to a still-solid pace in the fourth quarter.”

The BoC has a well-established pattern of conceding that current conditions are weaker than expected when the data leave it no choice but then offsetting that acknowledgement with forecasts of improving momentum on the horizon. There are benefits to using this approach. For example, if you’re in charge of managing inflation expectations, optimistic growth projections can help stave off complacency about continuing low interest rates that might otherwise fuel asset bubbles and undermine financial stability.

True to form, the Bank reduced its GDP growth forecast from 1.7% to 1.6% in 2020 but raised it from 1.8% to 2.0% in 2021. Its hope for improving momentum was underpinned by the following factors:

- “Canadian business investment and exports are expected to contribute modestly to growth, supported by stronger global activity and demand.” That assumption is underpinned by the Bank’s belief that businesses are less concerned about the “risks related to trade tensions and global growth.” Given that Phase One of the U.S./China trade deal is proving to be all hat and no cattle and that U.S. President Trump has vowed to turn his trade guns on Europe next, that sentiment could turn on a dime.

- “The BoC is also projecting a pickup in household spending, supported by population and income growth, as well as by the recent federal income tax cut.” We saw record levels of immigration in 2019, which are likely to continue. That will help fuel more spending overall, but income growth started to tail off at the end of 2019, and not everyone is convinced that the federal income-tax cuts the Bank references will have much impact.

- “In its January MPR, the Bank projects the global economy will grow by just over 3 percent in 2020 and 3 ¼ percent in 2021.” The BoC believes that global economic momentum is “bottoming out” after a period of “synchronous slowing.” That bottoming out was facilitated by 49 central banks cutting their policy rates 71 times by a total of 2,500 basis points in 2019. The BoC is hoping that these rate cuts will continue to bolster global economic momentum, but more than a decade of ultra-low rates has reduced the stimulative impact of each incremental rate cut, and that increases the likelihood that the recent uptick in global growth may end up being only a short-term sugar high.

The BoC’s most important forecast concerns inflation. Its primary mandate is to keep inflation “low, stable and predictable”, and BoC Governor Poloz has made it clear that the Bank will adhere to this mandate even if doing so creates negative side-effects in sub-sectors of our economy. Here is its latest assessment:

- “ … the output gap has widened in recent months.” The output gap measures the gap between our economy’s actual output and its maximum potential output. It is a significant inflation gauge because prices rise when the output gap closes, and the BoC will typically raise rates in anticipation of this occurring. A widening output gap portends reduced inflation ahead.

- “The Bank expects inflation will stay around the 2 percent target over the projection horizon, with some fluctuations in 2020 from volatility in energy prices.” A bit of a disconnect here because as per the point above, the widening output gap should ease inflationary pressures unless the Bank expects the gap to close (which it did not forecast).

- “Meanwhile, labour markets in most regions have little slack and wages continue to firm.” Last year we added more new immigrants than new jobs, and the federal government is hoping to increase our immigration numbers in 2020, above last year’s record level. That will help add labour capacity, and while average wages are still rising, their growth rate has showed early signs of slowing (down from 4.5% in November to 3.6% in December).

In its closing statement, the BoC said that it “will be watching closely to see if the recent slowdown in growth is more persistent than forecast”, conceding that the data haven’t yet made clear whether we are in a blip or at a turning point. The Bank will be keeping its eye on “developments in consumer spending, the housing market, and business investment.” With that in mind, I’ll be doing the same.

So, what does all of this mean for Canadian mortgage rates?

For borrowers in the market for a fixed-rate mortgage, these rates should continue to drop somewhat over the near term. The BoC’s more cautious stance and its acknowledgement of the widening output gap correlate with both lower growth and reduced inflationary pressures ahead.

For current variable-rate borrowers or for those considering a variable rate in future, a rate cut still appears a way off, because the Bank wants to see more evidence of slowing momentum before moving off the sidelines. That said, I continue to believe that the BoC will cut its policy rate, which variable mortgage rates are priced on, later this year (as I outlined in detail in my mortgage-rate forecast for 2020). The Bottom Line: The BoC did not cut its policy rate last week, but its more cautious tone pushed GoC bond yields lower, and several lenders responded by dropping their five-year fixed rates. If the five-year GoC bond yield remains at its current level, which marks a three-month low, expect other lenders to follow suit.

The Bottom Line: The BoC did not cut its policy rate last week, but its more cautious tone pushed GoC bond yields lower, and several lenders responded by dropping their five-year fixed rates. If the five-year GoC bond yield remains at its current level, which marks a three-month low, expect other lenders to follow suit.

Meanwhile, the BoC’s dovish shift should at least increase the odds that a rate cut may finally be on the horizon, which will be welcome news to variable-rate borrowers who haven’t seen a cut in more than four years.