Bank of Canada Governor Poloz May Want Higher Rates, But He Needs Stable Inflation

February 25, 2019The Case for Lower Canadian Mortgage Rates

March 11, 2019 If the Bank of Canada is “decidedly data dependant” as it claims, then it should put an end to speculation about near-term rate hikes when it meets this Wednesday.

If the Bank of Canada is “decidedly data dependant” as it claims, then it should put an end to speculation about near-term rate hikes when it meets this Wednesday.

Up until now, the Bank has ascribed our slowing economic momentum in the second half of 2018 to falling oil prices and predicted that it would prove transitory. In its most recent Monetary Policy Report (MPR), which I summarized here, the BoC drew a sharp contrast between the economic momentum in our oil-producing and non-oil-producing provinces. But more recent data have blurred that line, and it is now much harder to make the case that the current slow down is just an oil-price story.

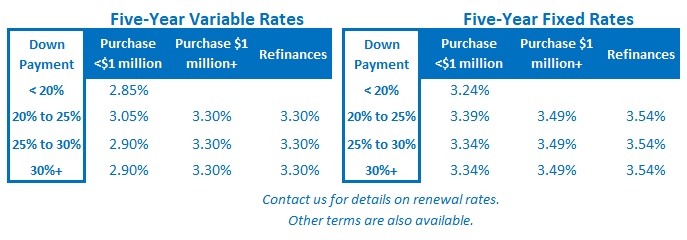

The Bank is not expected to change its policy rate, on which our variable mortgage rates are priced, when it meets this Wednesday. The real debate leading up to this meeting is whether the BoC will continue to talk about rates needing to move higher or concede that higher rates are no longer imminent.

The Bank’s coming statement will be important to fixed- and variable-rate mortgage borrowers alike. If it shifts to a more dovish policy-rate stance, we can expect Government of Canada (GoC) yields, on which our fixed-rate mortgages are priced, to fall in response. At the same time, a dovish shift would reassure variable-rate borrowers that the mainstream media’s warnings about sharply higher rates can finally be put to rest (which this contrarian has repeatedly argued since the BoC’s last rate hike in October).

Here are three key recent developments that are likely to impact the BoC’s evolving policy-rate view:

- Canadian inflation remains stable.

In his most recent speech (which I wrote about here), BoC Governor Poloz reminded us that “inflation is the sole target of [monetary] policy” and that the Bank will adhere to its singular mandate of keeping inflation low and stable even if doing so “may create side effects that make the economy vulnerable to new shocks”.

Last week we received the latest inflation data, for February, and it showed that overall inflation fell to 1.4% last month, marking a fifteen-month low. Furthermore, the Bank’s three key sub-measures of core inflation, which strip out the more volatile inputs that cause short-term swings in overall inflation, held steady at just under 2%.

The BoC’s decision to start hiking its policy rate in mid-2017 was based on the assessment that our economy was operating at close to its full capacity because that is the point when inflationary pressures start to build. At the time, the Bank argued that higher rates were needed to keep it from overheating farther down the road.

Our economy has continued to grow since then, albeit modestly, but inflationary pressures have not built up as expected. The two most obvious explanations for this are that our economy actually had more capacity for non-inflationary growth than the Bank estimated, and/or that the BoC’s policy rate was not as stimulative as it had previously believed.

Regardless of the reason, inflationary pressures are clearly not building to a level that would threaten price stability, and in the current environment it’s hard to imagine any justification for why they need to continue to move higher any time soon.

While it’s true that the BoC’s five 0.25% policy-rate increases since July 2017 may have helped to keep inflation under control, remember that the Bank estimates that it takes up to two years for the full impact of each rate hike to be absorbed into our economy (and we won’t hit the two-year mark for even the first of those rate hikes until this July).

Given that, the slowdown in the economic data that we have seen recently is occurring before the BoC’s recent rate hikes exert their full impact, and that leads me to conclude that inflation will soften further in the months ahead. Against that backdrop, the Bank’s immediate concern should be below-target inflation, not above-target inflation.

- Canadian economic momentum is slowing more rapidly than expected.

Last Friday we learned that our quarter-over-quarter GDP growth rate slowed to 0.1% in the fourth quarter of 2018 (which works out to a mere 0.4% on an annualized basis).

That was much lower than the 1.3% growth rate that the BoC forecast in its latest MPR and the details behind the data confirmed that our slowing momentum is no longer confined to our oil sector.

For starters, household spending and investment both contracted in the fourth quarter.

That wasn’t a complete surprise to the BoC, which expected that multiple rate rises and recent mortgage rule changes would slow consumer spending. But the Bank had repeatedly expressed hope that this lost momentum would be offset by a rise in business investment and export demand, and both of these areas also contracted in Q4 2018. Exports shrank by 0.1%, and business investment fell by 2.7% on a quarter-over-quarter basis.

Meanwhile, our best source of growth in Q4 came from inventories, which can be a misleading indicator because while this output gets counted in Q4, it is really just future production brought forward. Unless we see a surge in consumer spending and/or exports in early 2019, which is not yet evident, Q4’s inventory production will reduce our GDP growth in the quarters ahead.

Statistics Canada also revised its previous GDP growth estimates for Q1 2018, from 1.7% to 1.3%, and for Q2, from 2.9% to 2.6%, confirming that our economy wasn’t actually humming along as thought when the BoC hiked rates three times over 2018.

In summary, if our economic data had been telling the BoC that our waning momentum was an oil-sector story when it last met in January, it certainly isn’t doing that any more.

- U.S. Federal Reserve policy has taken a 180 degree turn.

The BoC can’t ignore material changes in the U.S. Federal Reserve’s monetary policies.

In December the Fed was forecasting three more rate hikes in 2019 and Fed Chair Powell warned that the Fed would continue reducing the size of its balance sheet on “autopilot”, even if doing so continued to push U.S. interest rates higher. U.S. financial markets swooned, and shortly thereafter Fed Chair Powell did a 180 degree turn. He now says that the Fed is likely done with raising its policy rate for the time being and that it might also stop reducing its balance sheet (and draining liquidity from financial markets) as early as this summer.

History will show whether Fed Chair Powell’s decision to back off was prescient (I believe strongly that it will eventually lead the U.S. economy to a worse fate), but over the short term, it did restore confidence and bolstered U.S. economic momentum.

Over that same period, the BoC has been less willing to abandon its hawkish rate stance, categorizing our slowing economic data as a temporary oil-sector induced set back and reiterating its belief that our economy will need higher rates over time if inflation is to remain stable.

That difference in rhetoric has helped to buoy the Loonie against the Greenback even though the U.S. economic data have been decidedly better of late. To wit, U.S. GDP quarter-over-quarter growth came in at 2.6% in Q4 compared to 0.1% in Canada, but surprisingly against that backdrop, and probably due to the BoC’s more hawkish stance, the Loonie has risen from 73 cents USD on January 1 to 75 cents USD last Friday. (The BoC’s forecasts in its latest MPR assumed that the Loonie would trade at 74 cents against the Greenback, so despite our economy’s recent tough sledding, our currency headwind has still managed to intensify a little).

Our near-term economic momentum is highly dependent on rising export demand, which requires a competitive currency. While no one at the BoC will admit it publicly, the Bank can’t maintain a more hawkish stance than the Fed for long. If BoC doesn’t weaken the Loonie, falling export demand (that will be difficult to recover) will do it for them.

The Bottom Line: Stable inflation gives the BoC room to turn dovish when it meets this week. Our recent economic data confirm that this shift is now appropriate, and if the BoC doesn’t oblige, our exporters will pay the price. For the reasons outlined above, I don’t expect variable mortgage rates to move higher until our economic landscape looks very different from how it does today, and if the BoC responds as expected, I think fixed mortgage rates are likely to move lower in the near future.