How Will the New USMCA Trade Agreement Impact Canadian Mortgage Rates?

October 9, 2018The One Word That Will Determine Where Canadian Mortgage Rates Are Headed

October 22, 2018 If you’re keeping an eye on Canadian mortgage rates, you would be wise to keep your other eye focused on what is happening south of the border.

If you’re keeping an eye on Canadian mortgage rates, you would be wise to keep your other eye focused on what is happening south of the border.

For better or worse, our economy is deeply linked with the U.S. economy, and while that means that strong U.S. economic growth is currently helping to fuel momentum here at home, it also means that rising U.S. inflationary pressures, if sustained, will work their way north of the border through our extensive trading relationship.

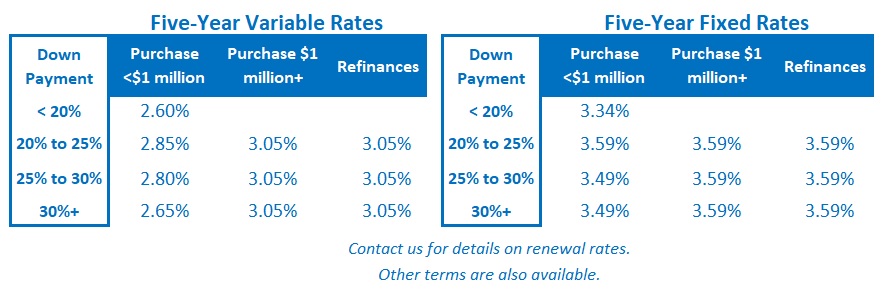

That will likely cause the Bank of Canada (BoC) to raise its policy rate, which our variable mortgage rates are priced on, more quickly than it would otherwise. At the same time, bond-market investors will bid up Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields, which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on, in anticipation of that outcome.

With that in mind, let’s look at the most recent U.S. and Canadian growth and inflation data.

U.S. GDP growth came in at 4.2% on an annualized basis in the second quarter of this year, marking the U.S. economy’s best quarterly growth rate in nearly four years. Over the same period, Canadian GDP grew by 2.9% on an annualized basis, and while that result wasn’t quite as impressive, it was more than double our 1.4% annualized rate in the first quarter.

U.S. inflation hit 2.9% on an annualized basis in the second quarter, which marked a six-year high after a steady march up from 2.1% at the start of this year. Over that same period, Canadian inflation hit 3.0% on an annualized basis, which was the highest it has been in nearly seven years and up significantly from 1.7% at the start of the year.

When improving economic growth coincides with steadily rising inflation, it’s a clear sign that an economy is operating at (or even above) its full capacity. And that’s why both the Fed and the BoC have been hiking their policy rates – to slow growth to a level that will bring overall inflation back down to about 2%.

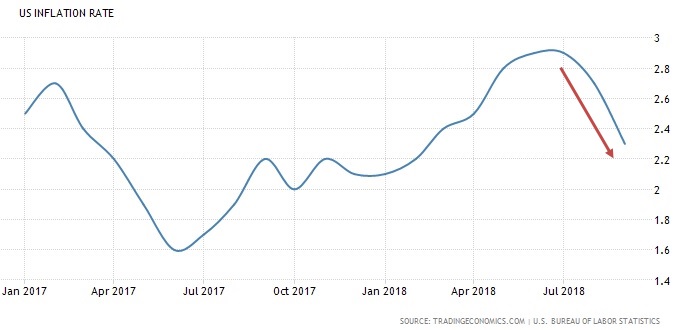

Those efforts appear to be working. Last week we learned that U.S. inflation dropped to 2.3% in September, down from 2.7% in August. When you look at the chart below, it sure looks like U.S. inflation has been brought to heel. By comparison, Canadian inflation cooled from 3.0% in July to 2.8% in August. (Our September result will be released this Friday.)

But we shouldn’t be too hasty in drawing this conclusion. In fact, last month’s lull may prove to be the calm before a coming U.S. inflationary storm. Here are my reasons for writing that:

- U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade tariffs are inherently inflationary for U.S. consumers, but the full impact of those price increases has not yet been felt. A good part of the second-quarter bump in U.S. GDP growth was the result of companies (both domestic and foreign) accelerating purchases ahead of the soon-to-be-enacted tariffs. As those inventories are exhausted, the next round of purchases will include the added tariffs. Only then will their full inflationary impact be apparent.

- The U.S. unemployment rate dropped to 3.7% in September, marking its lowest level in forty-nine years. Not surprisingly when labour is increasingly scarce, average U.S. wage growth is finally starting to show some life. It hit 2.9% on an annualized basis in August, marking its fastest pace in the last ten years. Expect U.S. labour costs to continue to rise for at least as long as the demand for labour outstrips supply and especially now that U.S. immigration policy is reducing the inflow of new immigrant labour.

- The U.S. federal government’s recent tax cuts and aggressive stimulus spending pushed its annual budget deficit to $833 billion during its 2018 fiscal year, which ended on September 30. That deficit is projected to rise to approximately $1 trillion in 2019. The U.S. Treasury has to keep issuing new debt to cover this massive shortfall, but it’s a bad time to be doing that. The two largest foreign buyers of U.S. government debt are China and Japan, and both have cut back their U.S. treasury holdings this year. Reduced demand for treasuries is helping to push their yields, and, by association, the yields on (and cost of) most other fixed-rate U.S. debt higher.

- President Trump’s decision to restore Iranian oil sanctions in August has upset the global supply/demand balance for oil, and other producers have been either unwilling or unable to pick up the slack thus far. Not surprisingly, market watchers are raising their oil-price forecasts and many are now speculating that we may see a return to prices of $100+ per barrel. If that happens, higher energy prices will have a pervasive impact on overall inflation.

In summary, several factors have the potential to push U.S. inflation higher over the near term, despite the apparent lull in the U.S. inflation data for September. If that happens, the Fed will have to accelerate its rate-hike timetable beyond the four additional quarter-point hikes that its policy makers are already forecasting between now and the end of next year.

The full impact of the Fed’s myriad rate rises will take time to accrue, but their impact on U.S. economic growth will be significant and we have already seen some of these effects in North American stock-market prices. The Fed has embarked on thirteen rate hiking cycles since 1950 and ten of them ended with a recession. If and when we get to that point, rates should then turn back down.

So how does current and expected U.S. inflation impact a Canadian mortgage borrower’s assessment of the age-old fixed-rate versus variable-rate question? If you opt for a variable-rate mortgage, you should be prepared for more BoC rate rises over the short term, albeit at a slower pace than those of the Fed. Over the medium term, if the rate hikes on both sides of the border slow growth to a point where our economies tip into recession, rate cuts are then likely.

The Bottom Line: Predicting that rates will rise and then fall is not rocket science. After all, that’s why they call it the business cycle. The key variable is the timing of when all of this will occur, and the best way to make that determination in the current environment is to keep a close eye on how the key factors outlined above are impacting U.S. inflation. Everything else should follow from that.