What the Heck is Happening to Five-Year Fixed-Mortgage Rates?

June 24, 2013U.S. Fed Chairman Bernanke Talks Bond Yields Down. Will Mortgage Rates Follow?

July 15, 2013 The U.S. Fed has been the proverbial bull in the North American bond market’s china shop since the start of the Great Recession, overwhelming market forces with the sheer scope and might of its unprecedented monetary-policy initiatives.

The U.S. Fed has been the proverbial bull in the North American bond market’s china shop since the start of the Great Recession, overwhelming market forces with the sheer scope and might of its unprecedented monetary-policy initiatives.

Thus, when the Fed announced several weeks ago that it would begin to taper its quantitative easing program later this year if the U.S. economic data continued to strengthen, it was easy to predict that subsequent data releases, especially positive ones, would trigger dramatic market reactions.

The latest U.S. employment report, which came out last Friday, provides the best and most recent example.

The data in the report were rock solid:

- The U.S. economy created 195,000 new jobs in June and better still, the April number was revised upwards by 50,000 to 199,000 while the May estimate was increased by 20,000 to 195,000.

- Average hourly earnings increased by 0.4% for the month and incomes rose by an average of 2.5% on a year-over-year basis, well above the current rate of inflation. This means that the average American’s purchasing power is increasing and since American consumers account for 70% of U.S. GDP, this was taken as a very encouraging economic signal.

- Once again the private sector carried the day, adding more than 200,000 jobs while the public sector shrank again, this time by 7,000 workers. In other words, on an overall basis, U.S. employment continues to strengthen in spite of continued U.S. public sector consolidation.

It came as no surprise that U.S. treasury yields surged on the news, or that Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields quickly followed. As a reminder, GoC bond yields have had a 98% correlation to movements in U.S treasury yields over the past several years.

But one, or even several, strong job reports to do not a sustainable U.S. recovery make. In fact, despite the latest banner U.S. jobs report, I remain convinced that the Fed will taper its quantitative easing (QE) program more slowly than most market watchers are expecting.

Consider the following:

- The Fed has repeatedly said that QE tapering will be entirely dependent on the economic data, and the forecast it linked to its tapering timetable was more optimistic than the forecasts given by 40 of 45 Wall Street economists who were recently surveyed. This is not new. The Fed has a well-established reputation for overly optimistic forecasts. For the Fed’s forecast to be realized, U.S. GDP will have to grow by about 3.2% in the second half of 2013 versus its average of 2% GDP growth over the last four years. Not impossible but in my opinion, highly unlikely.

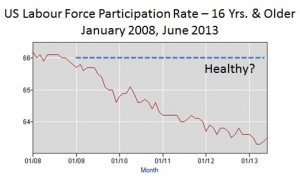

- The U.S. labour participation rate has fallen off a cliff since the start of the Great Recession. As the labour market heals, workers will try to re-enter the workforce and as they do, gains in employment will be offset by increases in the participation rate. To use the latest U.S. employment report as an example, while the U.S. economy added 195,000 new jobs last month, 176,000 discouraged workers jumped back into the market. As such, despite the big increase in newly created jobs, the unemployment rate stayed at 7.6%, unchanged for the month. Many people

don’t realize that there are a record number of long-term unemployed workers who aren’t being counted as officially unemployed at the moment. These workers must be absorbed back into the job market before U.S. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s “healthy” unemployment rate of 6.5% can be achieved. This will take many, many years.

don’t realize that there are a record number of long-term unemployed workers who aren’t being counted as officially unemployed at the moment. These workers must be absorbed back into the job market before U.S. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s “healthy” unemployment rate of 6.5% can be achieved. This will take many, many years. - The quality of new U.S. jobs still leaves much to be desired. The U.S. economy actually lost 240,000 full-time jobs in June and the only reason overall job growth was positive was that part-time employment increased by 360,000 to stand at an all-time record high (more than 28 million Americans currently work part time). More than half of last month’s newly created part-time jobs were in the retail and hospitality/leisure sectors (commonly referred to as ‘McJobs’). These are not the types of jobs that will fuel the American consumer’s resurgence, and while average incomes did rise 0.4% for the most recent month, that improvement is based on comparisons to already depressed income levels.

- No one is talking about it yet but the U.S. debt ceiling will need to be raised again in the fall. I haven’t seen anything from Congress to suggest that this will happen without more grandstanding and brinkmanship and I just can’t imagine that the Fed will choose to start tapering in the midst of another debt-ceiling fight.

- The U.S Treasury will issue fewer treasury bonds in the latter half of 2013 so technically speaking, the Fed can taper the dollar amount of Treasuries that it buys while still leaving the percentage of newly issued Treasuries it buys unchanged. In fact, if the Fed didn’t taper in response to the reduced amount of Treasuries being issued it would actually be passively increasing the size of its QE program (hat tip to David Rosenberg for that point).

To be clear, I think the Fed had no choice but to signal that it would begin tapering its QE program. A short read of economic history shows that when central banks engage in excessive monetary easing it invariably leads to credit and asset bubbles, followed by periods of rampant inflation. True to form, recent financial market distortions, such as the underpricing of credit risk, grew more and more extreme as investors increasingly expected the Fed to continue its QE program indefinitely.

There was really no easy way for the Fed to talk the market off its “QE forever” ledge. Unless the Fed’s tapering came with specific economic targets, its very possibility would trigger extraordinary market volatility as investors tried to guess at the Fed’s timing. But even the use of specific economic indicators wasn’t going to completely eliminate uncertainty because of the interconnectivity of the economic data. Unfortunately, there is simply no definitive, singular measure that the Fed can point to when trying to measure the true strength of the recovery. That’s why U.S. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke refers to a “healthy” unemployment rate of 6.5%. The number itself doesn’t tell the whole story.

This is the world where we now find ourselves. Canadian borrowers who are in the market for a five-year fixed rate mortgage could easily see this rate rise to 3.50% or higher over the next several months as the market swings wildly with each new U.S. economic data release. While I still think spikes in the five-year GoC bond yield will prove temporary, this will be no comfort to any borrower who ends up wrong-sided with their timing and who has to borrow at an inflated rate for five years.

Which brings me to the (surprisingly) still neglected five-year variable rate.

Given the air-tight correlation between U.S. and Canadian bond yields, borrowers who want a five-year fixed rate will be pitched and tossed about with every change in expectation around the Fed’s taper timetable. But in Canada, our variable rate only changes when the BoC raises its overnight rate, which it does in a much more calm and measured fashion.

So what is the current economic data telling us about when this might happen?

Consider the following:

- Canadian GDP growth has slowed sharply over the last three quarters.

- Our inflation rate stands at 1%, well below the BoC’s 2% target. Officially, the BoC is supposed to care just as much about correcting below-target inflation as it does about correcting above-target inflation.

- The Canadian economy lost 400 jobs last month, including a loss of 32,400 full-time jobs, and both average earnings and average hours worked shrank for the second month in a row.

- Our household debt to disposable income ratio has fallen over the most recent two quarters, at the same time that our savings rate has climbed to 5.5%.

All of these factors imply that the BoC should be thinking hard about lowering its overnight rate, not raising it, but that’s not even the biggest reason I think the BoC will stand pat for the foreseeable future.

Before I make my last point, here is a quick refresher. Five-year variable rates are calculated using bank prime rates. If you have a variable rate of prime minus 0.60%, that means that you are getting 0.60% off of today’s prime rate, which currently stands at 3.00%. Lenders move their prime rates in lock step with the BoC’s overnight rate, which currently sits at 1.00%.

The main reason I think that BoC isn’t going to raise its overnight rate is that U.S. and Canadian monetary policies are very tightly linked (because we trade so much with each other).

The Fed’s policy rate (which is equivalent to the BoC’s overnight rate) is currently set at 0%. That means the BoC’s overnight rate is currently 1% higher than the Fed’s policy rate and this has been one of the main reasons the Canadian dollar rose to par and remains within reach of par with the U.S. dollar. If the BoC raises its overnight rate even higher while the U.S. Fed leaves its 0% policy rate unchanged, the Loonie will appreciate further against the Greenback.

This would deal another broadside to our critically important and still-vulnerable manufacturing sector which has already been hammered by the appreciating Loonie. For that reason alone, I think it is highly unlikely that the BoC will raise its overnight rate at least until the U.S. Fed increases its policy rate.

So when will the Fed raise its policy rate you ask? At a minimum, this should not happen until the Fed has completely unwound its QE program. I started this post by explaining why I think the Fed’s predicted timetable for that is way too optimistic. If the market reacts violently when the Fed simply mentions the possibility of reducing its QE program in future, can you imagine what will happen when the Fed actually starts tapering, let alone unwinds QE altogether?

GoC five-year fixed rates were seven basis points higher last week, closing at 1.87% on Friday. Five-year fixed-mortgage rates can be found for as low as 3.19% but most lenders have offerings in the 3.29% to 3.34% range, depending on the terms and conditions that are most important to your particualr circumstances. Ten-year fixed rates were pushed higher last week as well but they can still be found for a shade under 4%. Given the incredible amount of bond-market volatility we have seen recently, borrowers are well advised to lock in a pre-approval so they know where they stand as soon as possible.

Five-year variable rates are being offered at rates as low as prime minus 0.60%. Despite all the recent increases to fixed rates, the BoC’s qualifying rate, which is used to qualify variable-rate borrowers, remains unchanged at 5.14%.

The Bottom Line: Five-year variable rate discounts are becoming more attractive at the same time that five-year fixed rates are rising. Furthermore, I think the factors that are driving fixed rates higher make it increasingly unlikely that the BoC will increase variable rates any time soon. For those reasons, if you’re comfortable taking on the risk that your mortgage payment might rise in future, I think the five-year variable-rate mortgage is more compelling than its fixed-rate alternative.