The BoC’s Latest Rate Cut Is Overshadowed By Trump’s Trade War

February 3, 2025US Inflation Heats Up Ahead of Trump’s Tariff-Related Price Increases

February 18, 2025

Trump announced he was slapping 25% tariffs on Canadian imports. Chaos has a way of slowing down time.

The Sword of Damocles did not fall on Trump’s first deadline, but it still hangs over us after he announced only a 30-day reprieve. Strangely, he cited the border security measures that had already been announced on December 17 as justification for the delay.

Nonetheless, the first shot in Trump’s trade-war has been fired, and the impacts on our economy are already evident. Businesses are planning to reduce their investment spending, and consumers who were already pulling back on spending are directing their purchases away from products made in the US.

Trade war headwinds pushed Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields lower last week. But, as I warned might be the case in last week’s post, lenders have been slow to reduce their fixed mortgage rates, which are priced on those bond yields. (In their defense, rising risk premiums have increased their funding costs, and their appetite to extend credit is understandably reduced during an economic shock.)

The burgeoning trade war will also likely keep the Bank of Canada (BoC) on a dovish footing. Its policy rate is now down to 3.00%, which is considered the mid-point of neutral-rate range. But the Bank will likely need to reduce it to a stimulative level of 2%, or less, to buffer against trade-related headwinds.

Last Friday, Statistics Canada released its latest employment report, for January. It estimated that our economy added many more jobs than were expected last month (76,000 actual vs 25,000 expected).

I don’t think this second consecutive month of stronger-than-expected job growth will concern the BoC in the least.

In its most recent communications, the BoC assessed that our labour market “remains soft” and noted that “job creation [has] lagged labour force growth for more than a year”. Our average wage growth also declined last month, despite our impressive headline result. It fell sharply from 4.0% in December to 3.5% in January on a year-over-year basis.

All of our key inflation gauges are back now within the BoC’s target range of 1% to 3%. In its latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR), the Bank projects that our economy will continue to operate with spare capacity until late 2026. Our economy’s benign inflation backdrop now gives it plenty of leeway to provide economic stimulus (via more rate cuts) if needed.

The latest US non-farm payroll report was also released last week. It estimated that the US economy added 143,000 jobs in January.

That result was below the consensus forecast of 170,000, but the shortfall was chalked up to temporary reductions in labour demand tied to the California wildfires and to colder-than-normal weather across much of the country.

The theory that last month’s disappointing US employment result was an anomaly was further supported by upward revisions to the initial non-farm payroll estimates for US job growth in Q4 2024. An additional 101,000 jobs were added to that quarter, confirming that US employment momentum was even stronger than previously believed.

Average US wage growth held steady at 4.1% on a year-over-year basis. But month-over-month wage growth increased from 0.3% in December to 0.5% in January, confirming that US wage pressures are increasing at the margin.

While the Canadian economy has plenty of room for non-inflationary growth, the US economy is operating much closer to its full operating capacity. (That is due in large part to historically high deficit spending by the US federal government and to a decline in the US household saving rate to near its lowest level in the past fifty years.)

In the context of a trade war, the fact that we need the US more than it needs us is at least partially offset by the fact that the US economy is currently more sensitive to additional price increases

Mortgage Selection Advice for Now

I expect further significant BoC rate cuts ahead.

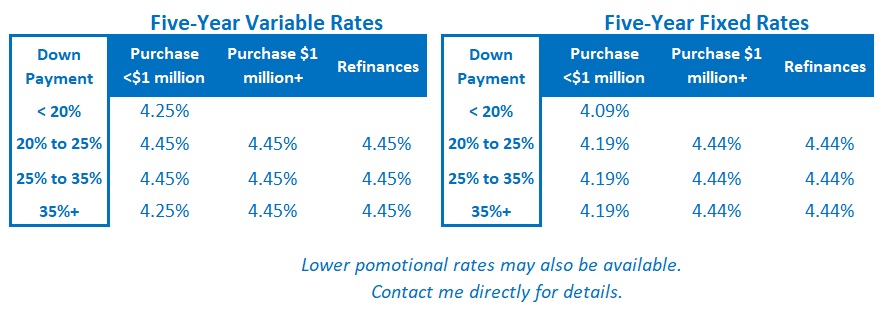

Today’s five year variable mortgage rates are roughly the same as their five-year fixed rate equivalents. I don’t think it’s a stretch to believe that the Bank will reduce its policy rate from its current level of 3.00% down to at least 2% during the current rate cycle.

By the BoC’s own estimate, its policy rate won’t provide stimulus to our economy until it reaches the 2% level. And when Trump’s threatened tariffs materialize (as they now have with steel and aluminum) we’re going to need all the help we can get.

A policy rate of 2% would also be consistent with the BoC’s past playbook. As per economist David Rosenberg, the Bank has reduced its policy rate to 2%, or lower, over its five most recent rate-cut cycles.

While I expect variable rates to outperform today’s fixed-rate options, I caution anyone choosing a five-year variable rate today to do so only if they are prepared for a rate rise at some point over their term. Five years is long enough for the next rate cycle to begin, and for variable rates to rise from wherever they bottom out over the near term.

On that note, while it may not seem so right now, the mortgage-rate risk associated with tariffs remains two-sided.

Bond-market investors have initially reacted to the trade war threat by pushing down bond yields, but tariffs are fundamentally inflationary. In the medium term, if higher prices persist, and if opportunistic companies enact non-tariff related price increases, price pressures will broaden.

In that scenario, both bond yields and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them will rise.

For borrowers who prefer the stability of a fixed rate, I think terms of between three and five years are the best options.

The rates available within that range of terms are now below their long-term averages. But shorter fixed-rate terms of one and two years still come with substantial premiums that I don’t think are worth paying.

Three-year fixed rates should allow enough time for Trump’s trade war to fully play out. A term of four years or longer will give borrowers rate certainty past the end of his term. (Assuming the US is still holding elections when we get to that point, and I’m only half kidding.) The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields finished the week about where they began it, holding on to the prior week’s sharp decline.

The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields finished the week about where they began it, holding on to the prior week’s sharp decline.

Today, there is room for lenders to reduce their fixed rates (despite higher funding costs tied to trade-war threats).

Five-year variable rate discounts were unchanged last week.

Our key inflation gauges are now all back within their target ranges and the BoC expects our economy to retain excess capacity until late 2026. That gives the Bank flexibility to cut rates further. With elevated downside risks tied to trade-war uncertainty, I expect more rate cuts to be forthcoming.